Chapter 1: Introduction & the Transition from High School to College

Chapter 1: Introduction & the Transition from High School to College

College: the romantic transition period from high school to work. Right? Every fall, as summer comes to an end, the media is flooded with images of 18-year-olds and their parents flocking to college campuses, loaded with personal belongings, ready to move into the dorms. The word “college” tends to make people think of young adults, recently graduated from high school, who will be living in residences on campus, studying with friends, and socializing together on the weekends. Individuals who have found and been accepted to the school that is the perfect fit for them. Let the magic begin.

Many young adults will have spent the summer preparing for the transition to college by cleaning bedrooms, sorting and downsizing belongings, revisiting memories and reading college student success guides. Transition guides include topics like: 10 things to do to be ready for college; dorm living; tips for classroom success; shopping for the things you will need in college; college and drinking; staying connected; and dealing with setbacks. All things the young adults need to know before striking out on their own for the first time. The 18-year-old, recent high school senior is seen as the “typical” college student.

However, the student profile for many colleges today is shifting. Young adults with few responsibilities other than college courses are becoming a shrinking demographic on many college campuses. Today’s college classrooms are increasingly becoming infused with students who have responsibilities beyond the classroom walls. Many are first-generation college students whose parents have not attended college and are not providing the students with firsthand information about the inner workings of college. Besides the basic foundational information surrounding college, many students need help understanding the information regarding the contextual aspects of college systems.

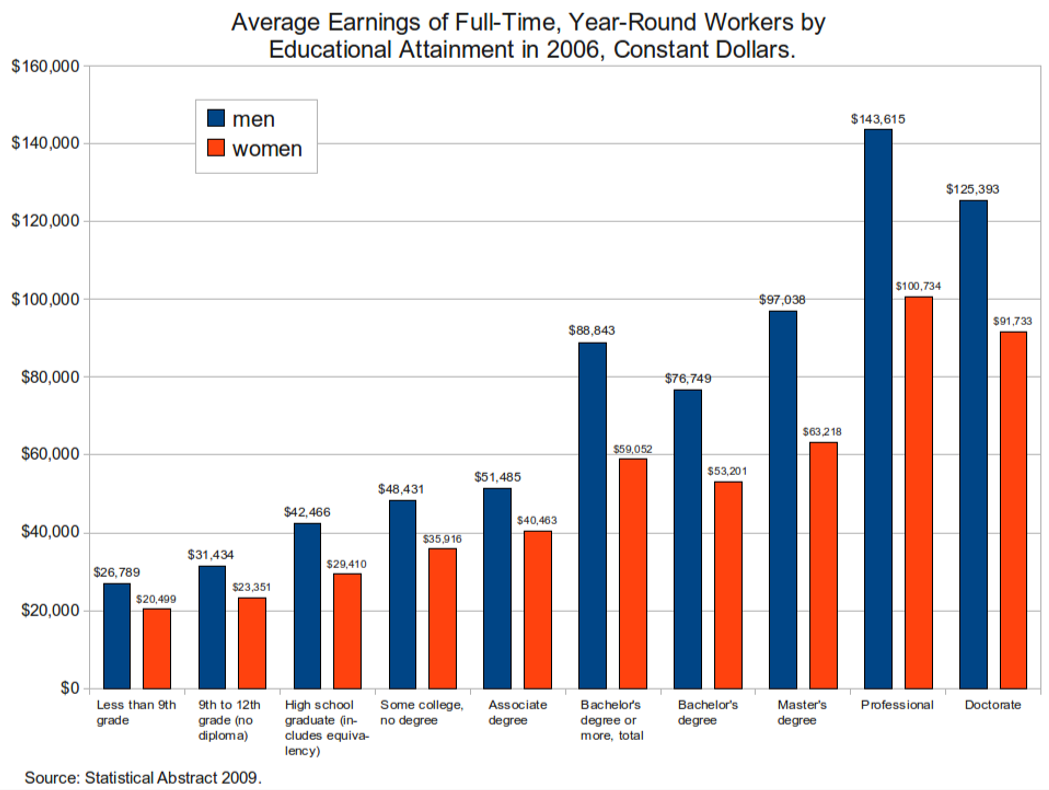

The cost of a four-year college education has risen roughly 150 percent since 1980. For this and other reasons, more and more students must take out student loans to finance their education. Upon graduation, many find they have accrued a sizable debt. Given the significant expense, some question the value of earning a college degree. However, along with the rising cost, the lifetime earnings difference between college and high school graduates has widened. The increased earnings potential for a bachelor’s degree allows a college graduate to recover the cost of college over time and eventually surpass the earnings of those with only a high school diploma.

The College Board estimates that for the 2010-11 school year the average cost of a four-year college education is $37,000 per year at a private nonprofit university and $16,000 per year at a public university. Over the past decade, the real cost of attending a four-year university increased an average of 3.6 percent per year. In contrast, for the same period, real personal income increased an average of only 2.1 percent per year. Consequently, more families turn to student loans for college funding. The College Board estimates that the percentage of students with federal student loans increased from 27 percent in 2004-05 to 35 percent in 2009-10. While estimates vary, a typical 2009 college graduate accumulated $24,000 in student loan debt, up 6 percent from the previous year.

For college to be a good investment, the benefits of a degree (e.g., higher pay) must outweigh the opportunity cost of attending. In this case, the opportunity cost is the sum of tuition and housing costs plus the wages that would have been earned from working directly after graduating from high school. Recent data show that while the cost of college increased, the labor-market value of a bachelor’s degree climbed to an all-time high. In 2008, college graduates earned on average 77 percent more than high school graduates. Also, from 1998 to 2008 the difference between the median earnings of those with a bachelor’s degree and those with only a high school diploma increased by approximately 23 percent. This increased earnings potential allows college graduates to “catch up” relatively quickly in terms of net lifetime earnings.

According to the College Board, recent college graduates who completely financed their education with student loans will earn enough by age 33 to cover the cost of those loans and match the to-date lifetime earnings of those the same age with only a high school diploma. Thus, the opportunity cost of attending college is recovered over time.

“Manage the Transition to College” from Effective Learning Strategies at Austin Community College. Authored by Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College. Available at: https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8434. License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

"Average Earning of Full-Time, Year-Round Workers by Educational Attainment in 2006, Constant Dollars." From Statistical Abstracts, 2009, available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Average_earnings_of_workers_by_education_and_sex_-_2006.png

The purpose of this course is to help you learn important skills that benefit you now, before you get to college. Just like riding a bike, skills like time management, studying, and developing self-awareness take time and practice. This book focuses on reflection, self-assessment, and action planning. At the end of the book, you will have a roadmap for how to build on your new skillset and success in college. More importantly, all of these skills are also lifelong skills.

Review the following table to review the major difference between High School and College.

Course differences:

High School | College |

| 6 hours each day, 30 hours a week are spent in class. | Approximately 12-16 hours each week are spent in class. |

| Average class is 35-45 minutes. | Class times vary from 50 minutes to 4 hours. |

| Class is usually a semester or 90 days. | Colleges have a semester or quarter system. Quarter systems meet approximately 11 weeks or 53-55 days. Semester systems meet approximately 16 weeks or 90 days. |

| Classes are arranged. | Each student decides his or her own schedule in consultation with an academic advisor. Schedules tend to look lighter than they really are. |

| Classes are structured and scheduled one after the other. | There are often hours between classes; class times vary throughout the day and evening. |

| Classes generally have no more than 35 students. | Class sizes vary from small to large. They may include 100 or more students. |

| Classes generally held in one building. | Classes are held at many different sites on campus. |

| Classes meet daily. | Classes may meet 1 to 5 times a week. |

| Missing classes for various reasons is permissible and you may still complete the course. | Missing classes may result in lowered grades or failing the class depending on course requirements. |

| Rigid schedule with constant supervision. | Students have more freedom and responsibility to create a flexible schedule. |

| Students may take same the subject all year. | Students will have new classes every quarter/semester and new textbooks. |

| General education classes dictated by state and district requirements. | Graduation requirements are complex and vary for different fields of study. |

| Textbooks are typically provided at little to no expense. | Textbooks can be expensive. The average cost per year is over $1,100 according to the College Board. Financial aid may cover costs. |

| Guidance is provided for students so they will be aware of graduation requirements. | With the help of academic advisors, students know and ensure they complete graduation requirements, which are complicated and may change. |

| Modifications that change course outcomes may be offered based on the IEP or 504 plan. | Modifications that change course outcomes will not be offered. |

Instructor differences:

High School | Postsecondary Education |

| Daily contact with teachers and support staff. | Classes meet less frequently, impacting access to instructors and assistance. Instructors are not always available to assist the student. Students can go to office hours for help. |

| Review sessions are often held prior to tests. Test questions are usually directed at the ability to recall what has been learned. Make-up tests are frequently available. | Students must work independently to prepare for tests. Review sessions by professors are rare. Students often must be able to apply information in new contexts. Make-up tests are unusual. |

| Students are usually corrected if their behavior is inappropriate. | Many moral and ethical decisions will arise. Students must take responsibility for their actions and decisions as well as the consequences they produce. |

| Students generally receive assignments in both written and oral form and may hand those assignments in during class time. | Students are often required to use email and the Internet for communication, class projects, submitting assignments, etc. |

| Teachers approach you if they believe assistance is needed. | Professors expect the student to initiate contact if assistance is needed. |

| Teachers are often available for conversation before, during or after class. | Professors typically have scheduled office hours for students to attend. |

| Teachers closely monitor a students' progress. | Professors may not monitor a student's progress but will grade based upon the student’s work or may not make any effort to discuss a student's performance in spite of failing scores. |

| Teachers provide information missed if you are absent. | Professors expect students to obtain notes from their classmates if they miss class. |

| Teachers remind students of assignments, due dates, test dates, and incomplete work. | Professors may not remind students of incomplete work. They expect students to read, save and consult the course syllabus (outline); the syllabus spells out exactly what is expected, when it is due and how it will be graded. |

| Teachers often write information on the board or overhead for notes. | May lecture nonstop. If they write on the board, it may be to support the lecture, not summarize it. |

| Teach knowledge and facts, leading students through the thinking process. | Expect students to think independently and connect seemingly unrelated information. |

Studying:

High School | Postsecondary Education |

| Students are expected to read short assignments that are then discussed, and often re-taught, in class. | Students are assigned substantial amounts of reading and writing, which may not be directly addressed in class. |

| Instructors may review class notes and text material regularly for classes. | Students should review class notes and text material regularly. |

| Study time outside of class may vary (maybe as little as 1-3 hours a week). | Students generally need to study at least 2-3 hours outside of class for each hour of class. |

| Someone is available to help plan study time (teachers, Spec Ed, parents). | Students are responsible for setting and following through on all scheduling and study time. |

Test-taking:

High School | Postsecondary Education |

| Frequent coverage of small amounts of material. | Usually infrequent. May be cumulative and cover large amounts of material. Some classes may require only papers and/or projects in lieu of exams. |

| Makeup tests are often available. | Makeup exams are seldom an option. May have to be requested. |

| Test dates can be arranged to avoid conflict with other events. | Usually, tests are scheduled without regard to other demands. |

| Frequently conducts review sessions emphasizing important concepts prior to tests. | Frequently conducts review sessions emphasizing important concepts prior to tests. |

Grades:

| High School | Postsecondary Education |

| Good homework grades may assist in raising the overall grade when test grades are lower. | Tests and major papers provide the majority of a student’s grade. |

| Extra credit options are often available. | Generally not offered. |

| Initial test grades, especially when low, may not have adverse effect on grade. | First tests are often “wake up calls” to let students know what is expected. |

Parent involvement:

High School | Postsecondary Education |

| Parents and teachers may provide support, guidance, and set priorities. Additionally, parent permission required (until 18 years of age). | Students are considered adults with decision-making authority. They set own priorities. Parent permission is not required. Due to FERPA, an institution cannot discuss with parents any student's information without permission from the student. |

| Parents and teachers often remind students of their responsibilities and guide them in setting priorities. | Decision-making is largely the student’s responsibility. The student must balance their responsibilities and set priorities. |

| Parents typically manage finances for school-related activities. | Students are responsible for money management and basic needs. |

"Difference Between High School and College", from GEAR UP Washington State Activity Guide Preparing Students for the Transition to College.

The transition from high school to college is an important milestone. Many students who live on-campus or commute experience a wide range of emotions during their first year at college. These emotions are normal and often occur in five stages. The following timeline includes examples of things students commonly face during their first year of college:

1. The Honeymoon Period. You may experience anxiety, anticipation, and an initial sense of freedom when you begin school. Homesickness and the desire for frequent contact with family are common. You may be getting to know roommates, making new friends on campus, and finding your way around. This period tends to be a time when you might incur many expenses for items such as textbooks, school supplies, and room decorations/furnishings.

2. Culture Shock. You begin to grasp the realities of adjusting to college. You begin to get feedback on your progress in class. You might experience shock at the workload, grades on first exams, or time management problems. You may feel out of place and anxious. For example, you might be dealing with the following items for the first time:

- Sharing a room with strangers.

- Budgeting time and money.

- Finding support and being a self-advocate.

- Managing a commute from home to school.

- Navigating a new community.

- Managing challenging coursework and a job.

This phase will pass. This feeling is very typical. There are free resources on campus to help-- you just need to ask.

3. Initial Adjustment. As the year goes on, you will begin to develop a routine. You will become familiar with campus life and new academic and social environments. If you are living on a campus, it is also completely normal for conflict to develop between roommates. You may be sharing a room with someone who is quite different from you. Most students are able to work things out when they discuss issues directly with one another or with a Resident Advisor.

If you are a commuter, you may have feel like you don’t fit in with the campus community or know the campus and its resources as well as your peers. Commuters also must balance their responsibilities at home and at school. It is important that you work to build relationships with your instructors and classmates. You can depend on outside support systems and also access the school’s academic and social services. You may reassess your time-management strategies, begin to explore majors or careers, and make plans with academic advisors. You might begin to plan to move off campus for next fall.

4. Homesickness or Loss of Confidence. With final exams finished, many students return home for winter break, and there may be concerns about how you will adjust to routines at home. For many, winter break is an opportunity to catch up on sleep and reconnect with old friends. You will also begin to receive your first semester grades and may experience joy, disappointment, or relief. Homesickness often occurs right after a vacation. You may become a bit insecure and have some misgivings about your new environment. You might wonder if you belong at college or if college is really all it is supposed to be. Homesickness is normal. As with any major transition period, students will have their ups and downs. Many students feel homesick at one time or another during their first year.

5. Acceptance and Integration. You finally feel like you are a part of the college community. You begin to think of it as home. You feel more confident with your time-management skills and experience less stress with exams. You will also be enrolling in classes for the fall and considering options for the summer. You might have mixed feelings about leaving for the summer and decide to stay to take classes and/or pursue summer work opportunities.

"The First Year in Five Stages: College" taken from GEAR UP Washington State Activity Guide Preparing Students for the Transition to College.

REFERENCES

- Blueprint for Success in College and Career. Authored by Dave Dillon. Provided by Rebus Community. Available at: https://press.rebus.community/blueprint2/ License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

- “Manage the Transition to College” from Effective Learning Strategies at Austin Community College. Authored by Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College. Available at: https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8434. License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/