The Blues: Bessie Smith

The Blues: Bessie Smith

This supplemental study and listening guide focuses on one of the best known blues musicians and composers, Bessie Smith, and a couple of pieces that feature her singing and the song she composed, "Lost Your Head Blues." The song "Downhearted Blues," recorded by Bessie Smith but composed by Alberta Hunter and Lovie Austin, is also covered here as an additional piece. Some historical background has also been provided as well as information about Smith's other songs and recordings.

Like ragtime, the blues is a pre-jazz style that originated in poor Black communities. The blues dates earlier than ragtime, tracing back to the mid- to late 1800s and emerging in the deep South, near the Mississippi delta. The style began as an orally transmitted tradition, meaning that songs were composed but remained unwritten, passed down from one musician to another. At first, the blues was instrumental music, played by a solo musician on acoustic instruments such as guitar, banjo, or accordion. Soon afterwards, vocal blues was also composed and performed. By the turn of the Twentieth Century, there were instances of home recordings of early blues singers; however, very few were made and survive today. As recording technology improved by the late 1910s into the 1920s, recording companies started taking an interest in producing commercial recordings. At this point in time, however, the blues became written down and its musical practices became formalized. Bessie Smith, the focus of this resource, became a recording sensation and a famous blues singer during the blues' final years as a popular music genre in the United States. Though a few of her precursors such as Charley Patton and Ma Rainey recorded, many did not. Smith's recordings represent the more formalized blues, which at times were straightforward blues or start with a couple of verses that give a backstory before the blues passage(s). Just a couple of Smith's contemporaries who also recorded include Mamie Smith (unrelated) and Robert Johnson.

The first instances of the blues cannot be traced, but these are the musical practices that led to the emergence of this genre:

- Black folksongs such as field hollers, ballads, spirituals, and ring shouts.

--Field hollers were used by slaves to communicate with each other while working in the fields;

--Ballads were based on European traditions for songs that tell stories;

--Spirituals were sacred (religious) songs that were sung not only during Black church meetings and formal gatherings such as sermons and funerals but also informally as musical praise and consolation;

--Ring shouts: A ritual that may include shouting, but mainly dancing (stomping) in a circle while clapping (performed religiously in Black churches and non-religiously, as a walkaround, out in fields). - West African griot and bolon player practices.

--Tracing back to the Middle Ages and likely earlier, griots in West African countries such as Mali, Ghana, and Nigeria were traveling musicians who sang stories about their communities that focused on praising kingdoms;

--Griot songs were also passed down orally and maintained genealogical details of kingdoms and important families as well as historical events;

--In contrast to griots, bolon players sang songs that could criticize people (their practices are also precursors to rap).

As vocal music, the blues took on lyrical content that may at first seem very obvious: its lyrics focus on being sad or blue. But the blues is also rich with meaning and expression, so mentioning the sad lyrical content barely scratches the surface. Though the lyrical content may be sad, it is capable of having dark humor as well as expressions of anger, frustration, and satisfaction. Blues lyrics or texts can be subversive, finding ways of expressing discontent about racism and racial violence in the United States that requires listeners to understand some coded language and the lowdown of being Black and living in the South. The blues also tends to use a slow tempo (the word "tempo" means the speed of the music).

The lyrics or texts of the blues has a specific structure. In this early recording of Bessie Smith, singing Alberta Hunter and Lovie Austin's "Down Hearted Blues" (1922), the first part of the song contains verses to give the backstory of her blues. After two verses, the blues passages take place. Just below are the lyrics for the first blues passage. Placed next to each line is a letter that helps to label the end rhyme:

Trouble, trouble, I've had it all my days (A)

Trouble, trouble, I've had it all my days (A')

It seems that trouble's going to follow me to my grave (B)

The first two lines of this blues passage are labeled A and A'. The text is exactly the same and together these two lines make a couplet. The last line, labeled B, is different from the first two lines and has a different end rhyme. This AA'B text structure is used in every blues passage. Another name for this structure is bar form. The lines labeled A may best be thought of as statement lines whereas the line labeled B serves as an answer. Here is why listening to "Down Hearted Blues" is important to do rather than just reading the text: The second A line of the lyrics, labeled A', has the same words and music; however, Smith inserts some slight variation. The A' label indicates that the text and music are the same as A but also that there's some slight variation taking place, too.

Listen once more to this song and this time think about the beat. Generally, the blues favors quadruple meter (four beats per measure). Tap, clap, or count along with the beats while listening. Play the song at first, listening to it, and don't begin counting along right away. Get a feeling for the beats and give it some time. The song's slow tempo and quadruple meter give a very steady sense of the rhythm. Like ragtime, which was covered in another supplemental study and listening guide, the blues uses syncopation, which means that instead of emphasizing the strong or expected beats (in quadruple meter, these would be beats 1 and 3), the weak or unexpected beats get stressed or accented instead (these are beats 2 and 4). While listening for the beat, give some weight to beats 2 and 4 while counting by either tapping, clapping, or saying those beats louder than beats 1 and 3. If you enjoy moving to the music, swing or sway with some emphasis on beats 2 and 4; this will give a good sense of the feeling of blues music, which became important to jazz as well.

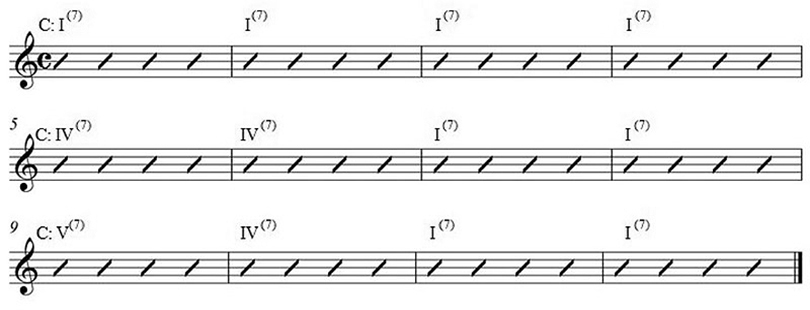

No musical background is necessary to understand that there's a pattern and structure. The Blues uses quadruple meter, which is four beats per measure. The blues passages contain a certain number of measures, which group the beats. In the blues and jazz, another name for measure is bar. The 12-bar blues is the most common musical structure of the blues, and this structure is studied here. To keep the blues interesting, composers sometimes write shorter and lengthier blues passages and songs; some are 8-bar blues while many extend the 12-bar blues to 16- or 24-bars. Blues allows for some variation, and varying the length provides some creative flexibility. To clarify, the structure of the accompaniment differs from the lyrical structure (AA'B) that was discussed earlier.

Typical instruments used for accompaniment include acoustic guitar, banjo, accordion, or (later) piano. All of these instruments can play more than one note at a time. A chord typically includes three pitches played simultaneously. Chords are used for accompaniment and are composed to fit with the melody. Not any chord can be used. The blues typically uses three chords most of all. The most important chord is the one labeled as Roman numeral I. This chord is the home chord (also the home key). In Western art music, including the blues, the home key is always established; even though the music may move away from it, a return to the home key is certain. The second and third chords used are labeled IV and V. These are also important chords in Western art music and help reinforce I as the home chord. The chord structure of the 12-bar blues is shown below.

Twelve-Bar Blues Progression. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Yehuda Lichtenstein Music, revised by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.The diagonal lines or slashes indicate the beat on which a chord is played (for example, guitar strums). Again, the home chord function of I is very important: The blues begins on I in the first measure and ends on I in the last measure. Another way to think of the accompaniment pattern is to just focus on the Roman numerals and combine the AA'B text structure discussed earlier:

Twelve-Bar Blues Progression. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Yehuda Lichtenstein Music, revised by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.The diagonal lines or slashes indicate the beat on which a chord is played (for example, guitar strums). Again, the home chord function of I is very important: The blues begins on I in the first measure and ends on I in the last measure. Another way to think of the accompaniment pattern is to just focus on the Roman numerals and combine the AA'B text structure discussed earlier:I - I - I - I (A)

IV - IV - I - I (A')

V - IV - I - I (B)

Again, syncopation is used (emphasizing beats 2 and 4 in each bar), but it isn't notated. The chords can be played straightforward with three notes (called triads); however, blues also encourages some slight variation with accompaniment. Even though I, IV, and V chords are used to keep the 12-bar blues structure, the (7) in the chart indicates that the composer or musician can add a pitch called a seventh to each chord, which gives the chords a more bluesy sound. The seventh is sometimes called a blue or blues note. Some chord substitution is also allowed to exist; in other words, a chord can be used to substitute for another one, creating a variation in the chord progression--the sequence of chords. Even though substitution is possible and variation is encouraged, too much substitution should be avoided (the piece still needs to sound like a blues piece, so many of the chords in the progression should remain unchanged). Variation in the blues between verses more often takes place subtly. For example, melodic tags (very short melodic details) may be added at the end of A, A', and B lines or the player/singer may start out softly and get louder and add more blues singing techniques as the piece unfolds.

What about vocal expression? Blues singing techniques include slides, scoops, shakes, as well as growling and wailing.

Slides are sometimes called "microtonal shadings," but it is easier to remember that this is a blues singing technique in which the voice slides up or down from one pitch to another. This technique is not only easy for vocalists to do; brass, woodwinds, and strings can also slide. But slides are not easy to perform on some instruments, such as piano. There is nowhere to play in between the keys. Nevertheless, pianists have mastered the illusion of sliding on their instrument. Two ways they can "slide" is by playing a glissando (quickly playing the notes between two keys spread out by an interval wide enough for doing so) or by playing grace notes (ornamental notes) before the intended notes. The grace notes occur quickly and tend to neighbor the intended note on the piano. It is certainly easy to tell with both ways what is being done to create a slide on the piano yet they sound bluesy.

Related to the slide are scoops, also called "dips," a blues singing technique that starts on the intended or target pitch, dips down quickly, then returns to the intended or target pitch. As with the slide, brass, woodwinds, and strings can perform scoops as easily as the voice whereas grace notes are often necessary when playing them on piano. Scoops usually include microtonal shading since one slides while dipping down and back up again. The in-between pitches of the scoop may be audible.

Shakes are also known as "quivers." When the voice shakes, the vocalist is using vibrato; in other words, the voice vibrates purposely. Shakes are often used to underscore the lyrical content of the blues.

Growling and wailing are self-explanatory. These are usually performed to add dramatic effect to the blues or because they are fun to perform and listen to.

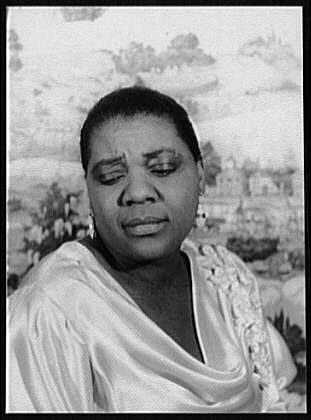

Bessie Smith (1894-1937) was nicknamed "The Empress of the Blues" for her powerful and expressive singing voice. She was born and raised in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Her parents died while she was still a child and her oldest sister raised her. Early on, she and her siblings worked to support her family. Her first musical training wasn't in school but rather as a street performer, buskering by singing and dancing with her brother.

Bessie Smith, Three-Quarter Length Portrait, Standing, Facing Front, with Left Hand Raised.

Bessie Smith, Three-Quarter Length Portrait, Standing, Facing Front, with Left Hand Raised. Source: Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection.

License: Public domain.

Portrait of Bessie Smith Holding Feathers.

Portrait of Bessie Smith Holding Feathers.

Source: Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection.

License: Public domain.

The best known photographs of Bessie Smith were taken by Carl Van Vechten in 1936.

In 1904, her oldest brother, Clarence, was hired by Moses Stokes' traveling troupe. In 1912, he returned with the troupe and arranged for his sister to audition. The troupe already had a singer, Ma Rainey (Gertrude Rainey, 1886-1939), who was nicknamed the "Mother of the Blues." Like several other performers in her time, Rainey was credited for inventing the blues; however, the blues existed before she was born.

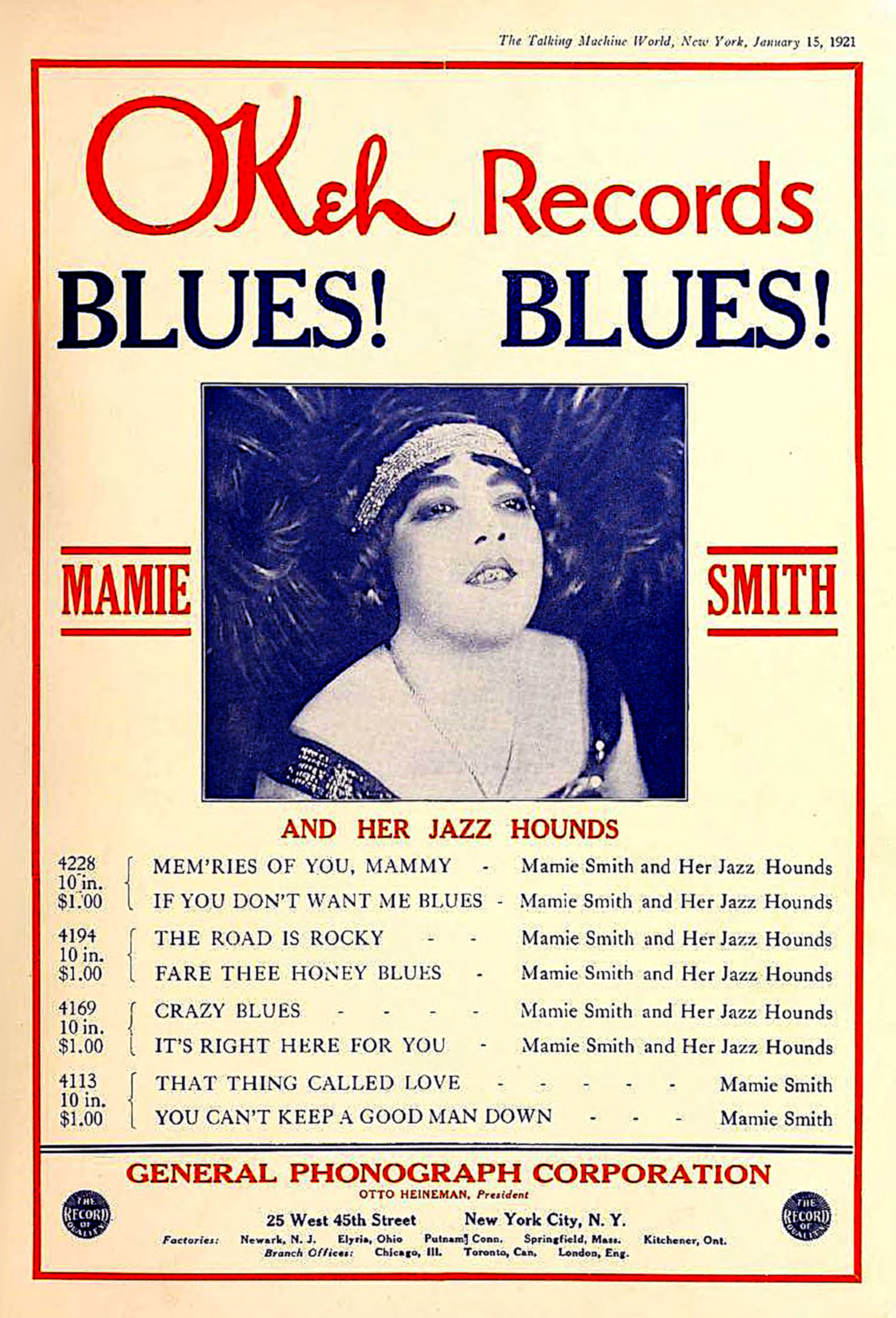

OKeh's Advertising at Talking Machine World:

OKeh's Advertising at Talking Machine World: Picture of Mamie Smith in the January 15, 1921 Issue.

Source: Internet Archive and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Unknown, Talking Machine World.

License: Public domain.

Ma Rainey didn't teach Smith how to sing the blues, but she nevertheless inspired and helped her early in her career. Rather than singing, Smith's first professional entertainment engagement was as a dancer, not a singer. By 1913, Smith's home became Atlanta, where she performed in several chorus lines at the 81 Theatre and developed her own act. By 1920, she became one of the most sought-after singers in the South.

In 1920, Mamie Smith, a blues singer who was unrelated to Bessie Smith recorded "Crazy Blues" (1918, composed by Perry Bradford) for the OKeh label in New York City. Within the year of its release, "Crazy Blues" sold nearly one million copies, mostly to Black listeners. Its success led to recording industry executives to search for Black female blues singers.

OKeh's Advertising at Talking Machine World:

OKeh's Advertising at Talking Machine World:

Picture of Mamie Smith in the January 15, 1921 Issue.

Source: Internet Archive and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Unknown. License: Public domain.

By 1923, Bessie Smith was signed to Columbia records for their race records series. Race records were marketed to Black audiences in the United States. Not only did they sell for less money than their parent labels, less investment was put into the recordings. Bessie Smith's first recording was "Cemetery Blues" (1923). Her first album included “Downhearted Blues” (with “Gulf Coast Blues” on the B-side). “Downhearted Blues” (also 1923) sold 780,000 copies within six months after its release; eventually two million copies were sold.

Smith's voice was strong, clear, and highly expressive, which made it ideal for recording during her time. Before continuing with her biography, let's briefly explore what recording and amplification technologies were like during her time.

Portrait of Bessie Smith.

Portrait of Bessie Smith. Source: Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection.

License: Public domain.

Though advances were made in recording technology in the early Twentieth Century, amplification technology trailed behind. For example, cinemas weren't equipped with speakers until the 1930s. Between the 1900s and 1930s, there were many advances in what we call record players. For example, the painting shown below, from 1898, titled "His Master's Voice" by artist Francis Barraud shows a wind-up disc gramophone. The painting was initially commissioned by the Gramophone Company in England, became the basis for their letterhead, and was turned into their trademark. Their American affiliate, the Victor Talking Machine Company, also adapted the image. By 1902, Victor's logo was based on the painting.

His Master's Voice (1888-1889).

His Master's Voice (1888-1889). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Francis Barraud, Victor Talking Machine Company.

License: Public domain.

This gramophone looks both different from and similar t0 the 1930s Victor phonograph shown below, which plays 78 rpm (long-playing) albums. Like earlier the wind-up disc gramophone, this phonograph plays records, uses a wind-up mechanism to operate it, and has a modified bell or horn used to amplify its sound.

Portable 78 rpm Record Player from British His Master's Voice label (Model 102, ca. early 1930s).

Portable 78 rpm Record Player from British His Master's Voice label (Model 102, ca. early 1930s). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Fredrik Tersmeden, Lund, Sweden.

License: CC BY-SA 3.0 and Gnu Free Documentation License.

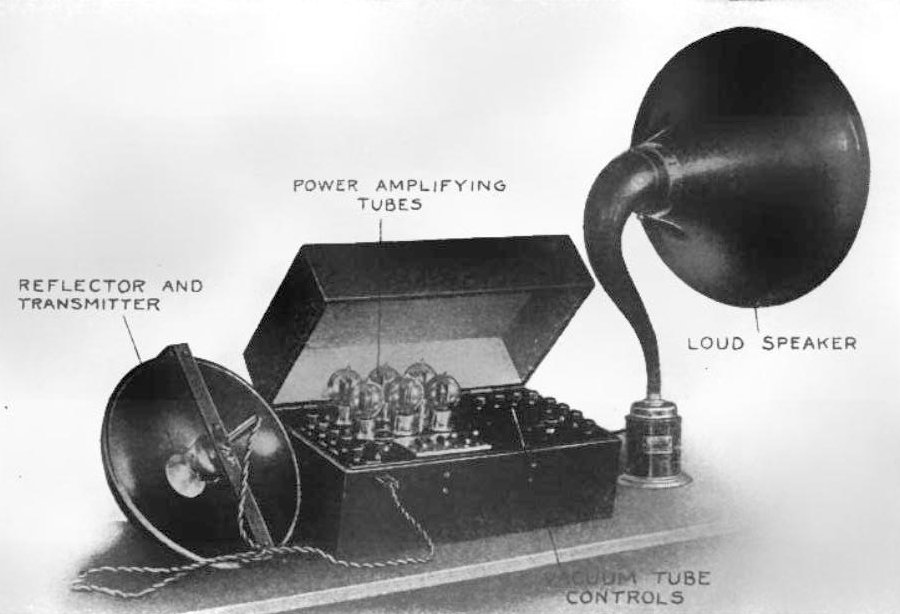

Pictured below is a public address system from about 1920 that was used for public speaking outdoors rather than for recording. The microphone in the photograph was called a "transmitter" then. In order to boost the audio signal, it was connected to a vacuum tube amplifier. Like the horn on the gramophone shown above, the horn (called the "loud speaker") was used to amplify sound. This machine was by no means powerful at all--it used just a 10-watt amplifier.

Early Vacuum Tube Public Address System (Before 1922).

Early Vacuum Tube Public Address System (Before 1922). Attribution: Unknown.

Source: Wikimedia Commons, downloaded from Austin Celestin Lescarboura (1922) Radio for Everybody (New York: Scientific American Publishing Co., P. 197 on Google Books).

License: Public Domain.

Here is a Western Electric double-button carbon microphone, which was developed in the early 1920s and became used often as a broadcast and recording microphone in the 1920s and 1930s, when Smith recorded. Sound engineers call this device a "ring and spring" microphone because of its appearance--the microphone itself is suspended by a metal ring with springs surrounding it in order to offset noise. The springs also provide some resonance to recordings. Even though this was a diaphragm microphone, the output was very low in comparison to today's microphones and its amplification was limited.

Western Electric Double-Button Carbon Microphone, Exhibit in the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Probably Model 357.

Western Electric Double-Button Carbon Microphone, Exhibit in the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Probably Model 357. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Daderot.

License: Public domain.

By the 1920s, Smith became the highest-paid Black entertainer of the time and could afford her own 72-foot-long railroad car for herself and her traveling entourage.

Bessie Smith.

Bessie Smith.

Source: Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection.

License: Public domain.

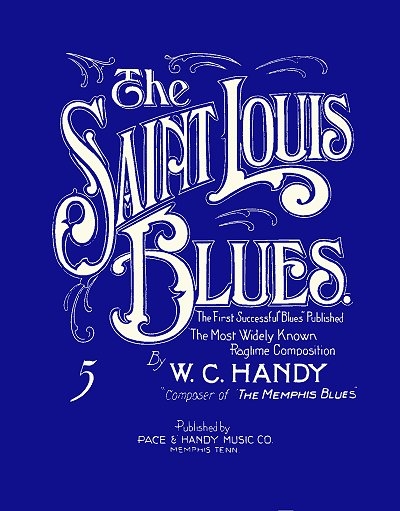

Though the popularity of recorded blues reached an end before the conclusion of the 1920s, Smith continued her career. She performed and recorded throughout Dixieland as well as during the early swing era. Ultimately, the Great Depression affected the careers of many musicians. Smith was a successful musician who wasn't paid nearly as much as lesser known contemporary white musicians. In 1929, she starred in Pansy on Broadway; however, the musical was a critical and financial flop. During the same year as Pansy, Smith performed the title song in the film St. Louis Blues (titled after the popular song by W. C. Handy).

Sheet Music Cover of

Sheet Music Cover of W. C. Handy's "St. Louis Blues" (1914).

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: W. C. Handy (composer), Pace & Handy Music Co. (publisher).

License: Public domain.

Although her performance and the film received critical acclaim, Smith still had to work her entire life. A film clip of her performance has entered public domain and can be viewed.

American Musical Short Film Featuring Bessie Smith: A Segment from the Two-Reel Short Film "St. Louis Blues" (1929).

Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Dudley Murphy (director). License: Public domain.

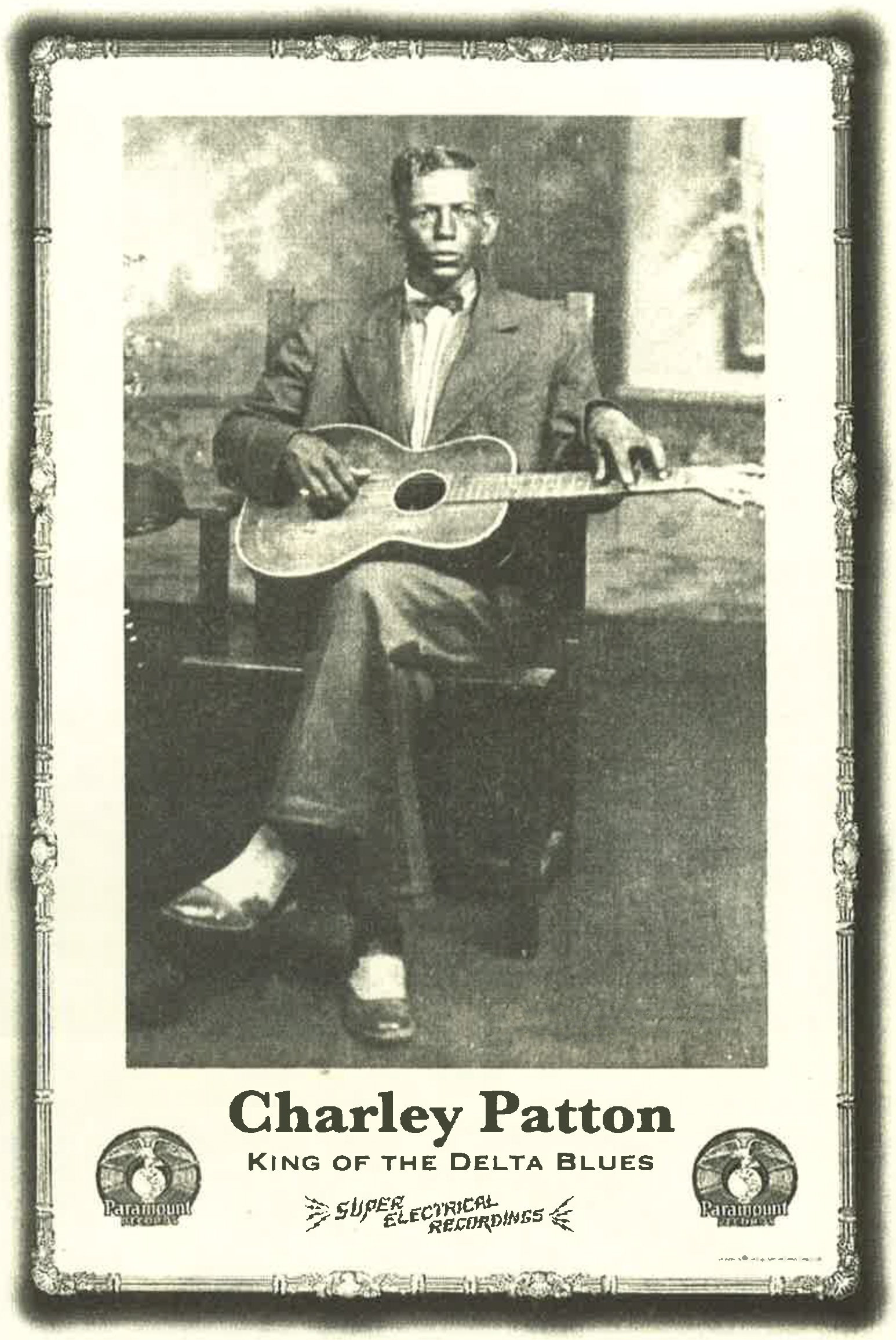

Smith's 1920s and 1930s recordings provide excellent examples of urban blues. Years after the blues emerged as an oral tradition, the genre became formalized and popularized through recordings. Country and Delta blues were generally less recorded because their appeal was limited to a rural market; however, blues songwriter-guitarist Charley Patton did record from 1929 until his death in 1934 and country blues gained a small resurgence of popularity during the Great Depression. Though his recording output was originally done in the Midwest, Patton, who was Black and Native American, eventually recorded for Vocalion, a major label in New York City. According to James E. Perone's Listen to the Blues! Exploring a Musical Genre (Greenwood, 2019) and several other sources, due to the poor quality of some of Patton's recordings, the masters for his earlier recordings with Paramount Records were unfortunately destroyed (Perone 2019, P. 11).

Publicity Photo of American Blues Musician Charley Patton for Paramount Records, Promoting Him as the "King of the Delta Blues" (1929-1930).

Publicity Photo of American Blues Musician Charley Patton for Paramount Records, Promoting Him as the "King of the Delta Blues" (1929-1930). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

License: Public domain.

By the mid 1930s and into the swing era, Bessie Smith was still performing. Moving away from the blues, Smith's last recordings were forward looking to the swing style. On the recordings, she was backed by several musicians who would become notable for swing, including Chu Berry (tenor saxophone) and Jack Teagarden (trombone); very briefly, Benny Goodman (clarinet) was a guest musician on one of these recordings.

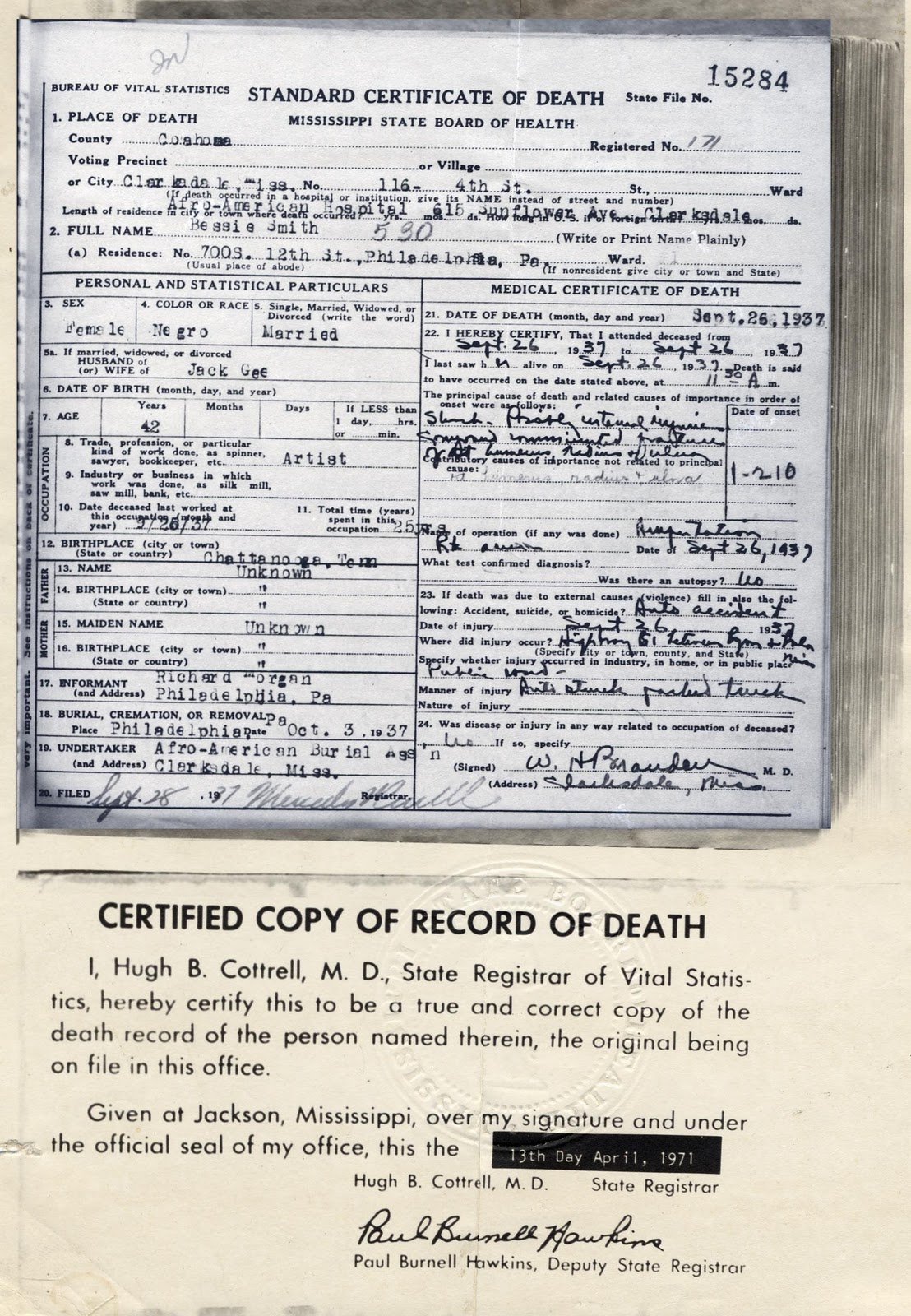

Bessie Smith died at age 43, resulting from injuries from two automobile collisions that took place while traveling to a scheduled performance. She was in the passenger seat of the car, likely with her right arm hanging out the window, as she and her lover, Richard Morgan, were traveling U.S. Route 61. The first accident was a side-swipe as Morgan, who was driving too fast, hit the rear of the truck that was ahead of them. The course of the collision reached Smith's side of the vehicle. Morgan had no injuries whereas Smith's arm was nearly severed. A surgeon from Memphis, Dr. Hugh Smith (no relation), was on the scene and later helped with providing his account of what happened. The account was published in Chris Albertson's biography, Bessie: The Empress of the Blues (London: Sphere Books, 1972).

Blues Trail Marker Located in Downtown Clarksdale, Mississippi: Riverside Hotel.

Blues Trail Marker Located in Downtown Clarksdale, Mississippi: Riverside Hotel. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Chillin662. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Above is a recent photograph of the Afro-American Hospital, where Smith died (now the Riverside Hotel). This site is now part of the Mississippi Blues Trail, a popular set of destinations for people who enjoy musical tourism.

For years, there was a story that Bessie Smith died due to blood loss from this injury because the hospital to where she was brought refused to save her because she was Black. Dr. Hugh Smith's account reveals that this story, perpetuated by record producer John Hammond's account in a November 1937 issue of DownBeat magazine and later Edward Albee's play, The Death of Bessie Smith (1959), was just partly true. According to Dr. Smith, Bessie Smith's injury to her arm was serious but not fatal. Dr. Smith asked his fishing partner, Henry Broughton, to move her to the side of the road. Broughton then called for an ambulance (Albertson 1972, pp. 192-93). During the long wait, Smith went into shock. Dr. Smith and his friend were going to take her to the hospital in his car, but just as they were ready, another car crashed into their car. Though the crash missed Bessie Smith, it wrecked both Dr. Smith and Bessie Smith's cars, and the couple driving the other car was badly injured (ibid., pp. 193-94).

Bessie Smith Official Death Certificate Issued by State of Mississippi.

Bessie Smith Official Death Certificate Issued by State of Mississippi. Source: Stomp Off! (blog) and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Hugh Cottrell. License: Public domain.

As her death certificate shows, Bessie Smith was taken to the G. T. Thomas Afro-American Hospital in Clarksdale, Mississippi. At this time, Mississippi was racially segregated, so Black people had to go to Black hospitals and white people had to go to white ones. Dr. Smith's account includes the important observation that Bessie Smith wasn't rejected treatment from a white hospital--he suggested that at the time no ambulance driver would have driven her to the white hospital (ibid., P. 196). What is left to interpretation is that Bessie Smith was a victim of racism in the Deep South because she had to wait to be transported to a Black hospital.

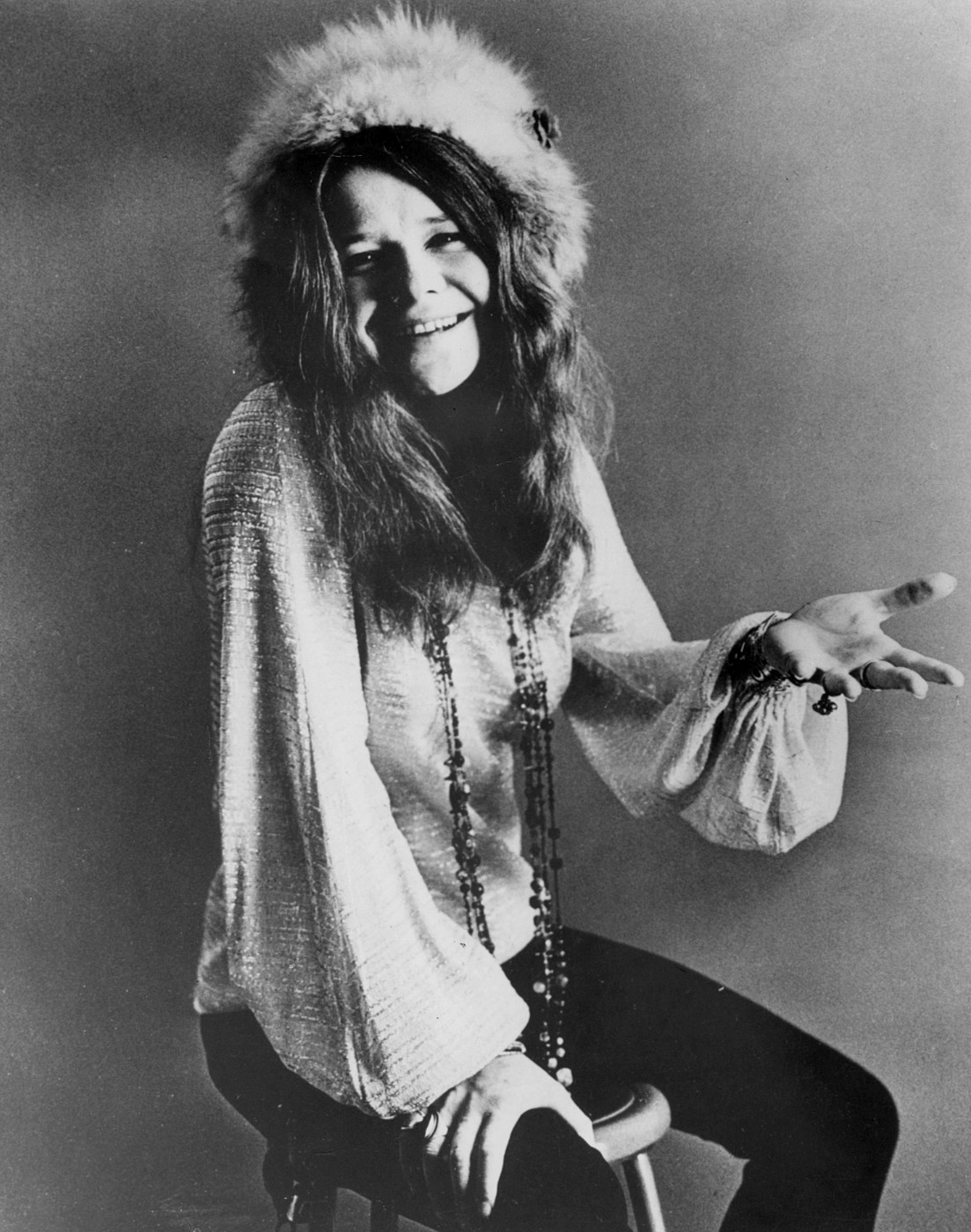

Smith's death was greatly mourned by thousands of people, who attended her funeral, and covered nationally in newspapers. Despite her celebrity, she was buried in an unmarked grave at Mount Lawn Cemetery in Sharon Hill, Pennsylvania. Her abusive ex-husband, Jack Gee, pilfered the money that was raised to purchase a headstone (ibid., P. 277). In 1970, singer Janis Joplin and Bessie Smith's former house worker, Juanita Green, purchased and successfully acquired a headstone for Smith.

Bessie Smith’s blues singing techniques and expression influenced many female and male singers. In her lifetime, she influenced Billie Holiday, but years later she influenced Janis Joplin, a 1960s classic rock singer who emulated not only her singing but also her sense of fashion and style.

Billie Holiday (ca. 1945).

Billie Holiday (ca. 1945). Source: Advertisement in Billboard Magazine, July 28, 1945, P. 2 and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Unknown, Billboard Magazine.

License: Public domain.

Holiday was most active during the swing era; however, she is best known as a torch singer and a singer of jazz-influenced pop standards. Joplin performed and recorded with the band Big Brother and the Holding Company before having her own solo recording career. Blues rock is a kind of classic rock subgenre. It fuses the blues with rock; blues is also the basis of a lot of classic rock songs--many classic rock musicians have also adapted the blues, including previously composed blues songs, in blues rock.

Publicity Photo from Photo Session of Janis Joplin.

Publicity Photo from Photo Session of Janis Joplin. Source: eBay Item (Photo front and back) and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: Albert B. Grossman Management (personal manager), New York.

License: Public domain.

Photo montage of Janis Joplin performing on the Television Program "Music Scene."

Photo montage of Janis Joplin performing on the Television Program "Music Scene." Source: eBay (Photo front and back) and Wikimedia Commons.

Attribution: ABC Television. License: Public domain.

Bessie Smith recorded mostly other composer's songs, making a special effort to record songs that were by or at least had lyrics written by women, but she is credited for composing "Lost Your Head Blues." This piece can be easily found on YouTube by just performing a simple title search. By the genre name "the blues," one would expect that the song content was just sad. The blues has more depth, though, if explored further. As Black music, the blues focused on many aspects of the Black experience, particularly in the South, during the early Twentieth Century. It began as rural music but spread in popularity and eventually an urban themed blues developed. Smith's recordings reflect urban blues much more than rural ones. The blues can be sadly humorous and it can also be subversive, having a message that runs beneath what the song seems to be about on the surface.

In so many ways, "Lost Your Head Blues" is representative of recorded blues as much as of Bessie Smith herself. "Lost Your Head Blues" was recorded by Smith in 1926--just a year before Louis Armstrong and Lillian Hardin Armstrong would record the Dixieland piece "Hotter Than That." Unlike rural blues, which used voice and guitar, this recording features Smith as the vocalist, accompanied by piano and trumpet. The lyrics have just entered public domain, so part of them can be shown here. After a short trumpet and piano introduction, the first blues verses are sang:

I was with you, baby, when you didn't have a dime

I was with you, baby, when you didn't have a dime

Now since you got plenty money, you have throwed your good girl down

Once ain't for always and two ain't for twice

Once ain't for always and two ain't for twice

When you get a good girl, you'd better treat her nice

Notice how the first line gets repeated and is followed by a third line with different lyrics. This is called AAB form (the first two lines are A and the last one is B). It's fairly straightforward how this form works with just the words, but the words are only one part of the song. When you play this song, notice that the music for the first two lines is very close to the same--not identical, but very close. Then the music to the last line is different. A better way to think of the form is like this: A1A2B or AA'B. This way, you're communicating with others that you have the same text (A) but slightly different music (A1 or A'). The AAB form helps add a sense of organization to the song on a structural level. The text structure is always statement-repeated statement-answer.

Typical of the blues, "Lost Your Head Blues" is in quadruple meter--four beats per measure. When you listen for the beat, play the music a bit at first and then try to see if you can hear a pulse. Tap or clap along with the beat; it will help you to learn this song for the exam. This song is in a typical form called "12-bar blues." This means that there are twelve measures in each blues verse. The singer performs through most of the lines, but sometimes the instruments play by themselves. Each line of text represents four measures. Here, Smith begins with her line and the instruments seem to conclude it for her. To accompany her, the blues has a set pattern that is strongly characteristic of the musical genre. The first line (A1), which is the first four measures of the blues, is in a home key (called the tonic or I). When she repeats the line (A2), the accompanying chords move. This adds some listening interest. They move to a new chord called the subdominant or IV. The change of chords is slightly different music from the first line. This move is brief, and her line (still A2) ends in the home key (I). Her final line shows the most movement, up to a dominant or V chord, then passing through the subdominant or IV chord, and then reaching and concluding on the home key, the tonic or I chord. The 12-bar blues musical structure can be represented this way (each line represents a bar or measure--you can think of the chord as being played on the beat, so strummed or played four times per measure):

|| I | I | I | I || (A1)

|| IV | IV | I | I || (A2)

|| V | IV | I | I || (B)

You might not need to know the Roman numerals or chords yet, but you should be aware of the musical pattern and how the chords sometimes stay still and then move. To make the piece more bluesy sounding, Smith slides up and down pitches. She also scoops or dips her voice, starting on the right note, moving down, then returning to the right pitch again. Other blues singing techniques can be hear in "Lost Your Head Blues." Smith shakes or quivers her voice on some words, often to give a sense of the meaning of the word musically and how desperate or sad she's feeling. Smith almost wails during the song--it doesn't quite get there, but on the word "days" it comes close. It cannot be stressed enough how important these blues singing techniques are: Jazz builds on the blues as does later rock and roll.

Beyond listening for the beat, listen for how Smith uses these blues techniques. If you are keeping up with the beat, try to hear whether or not she starts before or after the downbeat. Starting before the down beat adds a sense of urgency or anxiousness to the music, which would make sense for this kind of blues song.

"Lost Your Head Blues" was composed by Bessie Smith herself. It's uncertain, but there's a story that she and her ensemble created the song on the spot. Apparently, they were supposed to record more minutes of music and had to put a song together quickly.

Although our main focus is "Lost Your Head Blues," another piece that is often covered in college courses is "Downhearted Blues" (composed in 1922). As mentioned earlier, even though Bessie Smith was a composer, she recorded many songs by others and is known for her recordings of women composers and lyricists. Lovie Austin composed the music and Alberta Hunter wrote the music to "Downhearted Blues." Hunter recorded the song in 1922. She was a singer in King Oliver's band in Chicago--Louis Armstrong had also played in this band and Oliver was once his mentor.

"Downhearted Blues" is a good example of a popular song that uses the blues after a couple of verses. The song's vocal part starts with an introduction with the opening line, "Gee, but it's hard to love someone when that someone don't love you." This line came from Hunter's performance at the Dreamland Café, a Black jazz cabaret and famous performance venue in Chicago. Smith recorded this song a year after Hunter, in 1923, and it is her rendition that has become the most famous recording.

Listen for the entrance of the blues passages. These begin with the line "trouble, trouble...." The same blues techniques mentioned previously in this source are applied in this recording, which features Smith accompanied by Clarence Williams on the piano. Listen for Williams' piano introduction before the two introductory verses. The blues passages start where you hear "trouble, trouble." Notice how Smith's voice slides and shakes on this word. The rest of the song, the 12-bar blues, uses the AA'B blues text structure. All of the lyrics can be easily found on the Internet. Tap or clap along to see if you can hear the beat. Here it is in quadruple meter (four beats per measure). The song concludes with Williams, who plays a brief outro on piano.

The following information is listed here by order of appearance on this page (from top down to bottom):

Acoustic Guitar with Seashell. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith. License: CC BY-SA. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acoustic_Guitar_with_Seashell_Inlay.jpg.

Twelve-Bar Blues Progression. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Yehuda Lichtenstein Music, revised by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith. License: CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=103325205.

Bessie Smith, Three-Quarter Length Portrait, Standing, Facing Front, with Left Hand Raised. Source: Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection.

License: Public domain. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/pnp/van/5a52000/5a52600/5a52645v.jpg and https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bessie_Smith,_three-quarter_length_portrait,_standing,_facing_front,_with_left_hand_raised_LCCN2004663575.jpg.

Portrait of Bessie Smith Holding Feathers. Source: Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection. License: Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49459918 and https://loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.09571/.

Gertrude Pridgett “Ma” Rainey. Source: The New York Times and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Unknown. License: Public domain.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/12/obituaries/ma-rainey-overlooked.html and https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7740906.

OKeh's Advertising at Talking Machine World: Picture of Mamie Smith in the January 15, 1921 Issue. Source: Internet Archive and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Unknown, Talking Machine World. License: Public domain. https://archive.org/details/1921-USA-Archives-1921-01-15-The-Talking-Machine-World/page/n30 and https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81808008.

Portrait of Bessie Smith. Source: Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection. License: Public domain. http://lccn.loc.gov/2004663572, http://cdn.loc.gov/master/pnp/van/5a52000/5a52600/5a52642r.jpg, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004663572/, and https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66207348.

His Master's Voice (1888-1889). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Francis Barraud, Victor Talking Machine Company. License: Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1793229.

Portable 78 rpm Record Player from British His Master's Voice label (Model 102, ca. early 1930s). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Fredrik Tersmeden, Lund, Sweden. License: CC BY-SA 3.0 and Gnu Free Documentation License. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portable_78_rpm_record_player.jpg.

Early Vacuum Tube Public Address System (Before 1922). Attribution: Unknown. Source: Wikimedia Commons, downloaded from Austin Celestin Lescarboura (1922) Radio for Everybody (New York: Scientific American Publishing Co., P. 197 on Google Books). License: Public Domain. https://books.google.com/books?id=QwY9AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA197#v=onepage&q&f=false and https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25731868.

Western Electric Double-Button Carbon Microphone, Exhibit in the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Probably Model 357. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Daderot. License: Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35103283.

Bessie Smith. Source: Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection. License: Public domain. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004663572/ and https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18179737.

Sheet Music Cover of W. C. Handy's "St. Louis Blues" (1914). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: W. C. Handy (composer), Pace & Handy Music Co. (publisher). License: Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7620415.

American Musical Short Film Featuring Bessie Smith: A Segment from the Two-Reel Short Film "St. Louis Blues" (1929). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Dudley Murphy (director). License: Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Louis_Blues_(1929).webm.

Publicity Photo of American Blues Musician Charley Patton for Paramount Records, Promoting Him as the "King of the Delta Blues" (1929-1930). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Originally published and distributed in 1929–30 by Paramount Records. This image is from the following reproduction: John Tefteller (2003). "Gold in Grafton! Long Lost Paramount Photos, Artwork, 78s Surface after 70 years!" 78 Quarterly, no. 12. P. 12. The image has been retouched to remove an inaccurate copyright notice. Attribution: Unknown, Paramount Records. License: Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=102511493.

Blues Trail Marker Located in Downtown Clarksdale, Mississippi: Riverside Hotel. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Chillin662. License: CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69837505.

Bessie Smith Official Death Certificate Issued by State of Mississippi. Source: Stomp Off! (blog) and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Hugh Cottrell. License: Public domain. http://stomp-off.blogspot.com/ and https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12854317.

Billie Holiday (ca. 1945). Source: Advertisement in Billboard Magazine, July 28, 1945, P. 2 and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Unknown, Billboard Magazine. License: Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50771522.

Publicity Photo from Photo Session of Janis Joplin. Source: eBay Item (Photo front and back) and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: Albert B. Grossman Management (personal manager), New York. License: Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21497927.

Photo montage of Janis Joplin performing on the Television Program "Music Scene." Source: eBay (Photo front and back) and Wikimedia Commons. Attribution: ABC Television. License: Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32432831.