Chapter 1 Section 3: Nutrition and its Role in Health

Chapter 1 Section 3: Nutrition and its Role in Health

Section 3

Nutrition and its Role in Health

Learning Objectives |

|

Macronutrient role in disease development

While understanding the differences of the kcal association of macronutrients is important, it is even more important to understand how macronutrient and kcal imbalance contributes to weight gain, disease development and genetic alterations.

Carbohydrates

Sugar

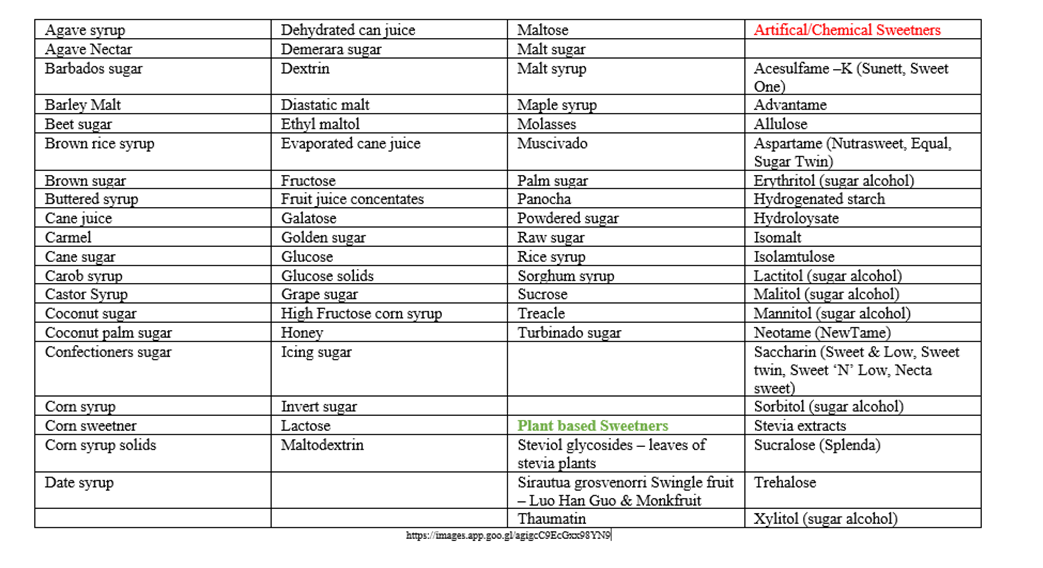

One of the main sources of carbohydrates is sugar and this substance has numerous names to its formulation (Table 4). Because of the multiple names for sugar, it is difficult for individuals to know that the diet food product that they are eating and thinking is a healthy alternative is actually not. As consumers we are aware of two highly familiar sugar products, glucose and fructose. Fructose is commonly known to occur in fruit and some vegetables, and this has been the source of its diet association until the 1960’s when high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), derived from the corn starch became the dominant source associated with the Western diet (Herman & Birkham, 2021).

Aren’t the grams of sugar on the package all that matters? Although glucose, fructose and sucrose are all calorically equivalent, not all sugars are metabolized the same way (American Society of Nutrition). It is this difference that can lead to epigenetic changes and disease development. For instance, when consuming glucose, the liver is initially bypassed, and the glucose reaches systemic circulation to be used by tissues such as the brain and muscles unchanged or metabolized. If excess glucose is consumed in the diet, the body will first store as glycogen in the liver, and secondarily as fat.

Glucose is a monosaccharide, meaning it’s a simple unit of sugar that is one molecule and what our bodies use for energy and is stored as glycogen in our muscles and liver. It is also the primary energetic and synthetic fuel for most tissues and cell types in the body. In processed food, glucose is often added in the form of dextrose which is derived from wheat and/or corn. Because glucose is already in its simplest form, it is directly absorbed from the small intestine into the circulatory system and quickly signals the release of insulin for cellular transport. This quick release and transport is what can cause the high/low energy feeling that people experience from consuming high glucose containing foods.

Fructose, also a monosaccharide, is a naturally occurring sugar in fruit and root vegetables. In food products we typically see this as High Fructose Corn Syrup. High -fructose corn syrup is made from cornstarch and contains more fructose than glucose equivalents. This product is easily absorbed in the intestines directly into the portal vein during digestion. When cleared by the intestines it is converted to glucose in the liver, our bodies use it for energy, its polymeric storage form of glycogen, or to fatty acids and is stored as triglycerides (Harmon & Birnham, 2021).

Fructose though will not immediately signal insulin release from the pancreas as glucose does, the liver must convert it first into glucose before the signaling transpires. High consumption without energy expenditure by the person consuming will lead to an increase adipose tissue stores, development of fatty liver disease and potential metabolic syndrome development.

Sucrose, is a sugar molecule made up of both glucose and fructose, so sucrose is called a disaccharide. This type of sugar is found in fruit, vegetables and what is commonly called table sugar which is derived from sugar cane or sugar beets. It is this type of sugar product that is frequently added as the “sweetener” to cookies, ice cream, candy, cakes etc. Digestion and breakdown of sucrose begins in the mouth with the majority of it occurring in the small intestine. The enzyme sucrase, which is made by the lining of your small intestine, splits sucrose into glucose and fructose. The glucose and fructose are then absorbed into your bloodstream where they are transported into the general circulation for immediate use (glucose) or to the liver (fructose) to complete the metabolic conversion process (Harmon & Birnham, 2021).

Unlike glycolysis, the catabolism of fructose (fructolysis) bypasses major regulatory steps of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. Major pathways of fructose metabolism are conversion to glucose and lipids. Therefore, excessive fructose intake would result in increased portal fructose concentrations that stimulates endogenous glucose production and lipid synthesis in the liver, which is associated with metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), obesity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Merino, et al. 2019)

Table 4: Other names for sugar

Fructose, is a simple sugar, which is most commonly consumed in the form of sucrose. The metabolism of this product engages a different pathway than glucose. When fructose is consumed, it is exclusively metabolized in the liver, where a particular enzyme, fructokinase, will allow for the uptake of fructose (Herman & Birkham, 2021). Fructose metabolism as a whole lacks many of the cellular controls that are present in the glucose metabolism, which allows for unrestrained lipid synthesis.

An overload of fructose in the liver will lead to de novo lipogenesis and subsequent lipid droplet accumulation in the liver. With these high levels of fructose, the increase in lipid accumulation consequently decreases the breakdown of fat in the liver. This intra-hepatic lipid will promote the production and secretion of very low-density lipoprotein 1 (VLDL1) leading to an increase in post-prandial triglycerides (Herman & Birkham, 2021). A vicious cycle occurs effecting insulin resistance as well. The lipid in the liver will increase insulin resistance resulting in increases in circulating diacylglycerol. Additionally, the insulin resistance will lead to further lipid deposit in the liver with sugar having a greater propensity to turn to fat. A downstream effect of increased apoCIII and apoB will lead to muscle lipid accumulation, and end in whole body insulin resistance. All of this metabolic dysregulation results from the direct route fructose initially takes to the liver (Merino et al., 2019).

Artificial Sweeteners

Sugar alcohols are actually not a sugar nor an alcohol; they are a form of carbohydrate derived from fruits and vegetables though the majority of sugar alcohols are synthetically manufactured (Sloan 2023). They are a little lower in calories than traditional sugar and are reported to not potentiate dental caries or cause sudden increases in blood glucose or insulin spikes when consumed as they are slowly broken down in the gut. One of the key attractions of these products is that they have a higher sweetness intensity per gram than natural sugar, ranging from 40% to 80% higher sweeting taste. (Sloan, 2023). These types of sweeteners are typically found in sugar free products, ice cream, chewing gum, cookies, and beverages. Sugar alcohols do not come without side effect and when consumed in high amounts can precipitate gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea and loose stooling. These products also affect the gut microbiome through their utilization by microbes as a source of “food” leading to increased fermentation and the production of gas. Individuals with sensitive GI tracks, these products should be used sparingly.

Key take away

Overconsumption of high-fat foods and sugar-sweetened beverages is a risk factor for developing obesity, type 2 diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Most food and beverages are sweetened with table sugar and/or high-fructose corn syrup, both of which contain fructose and glucose. Though both sugars promote fat build-up in the liver, the liver metabolizes fructose and glucose differently.

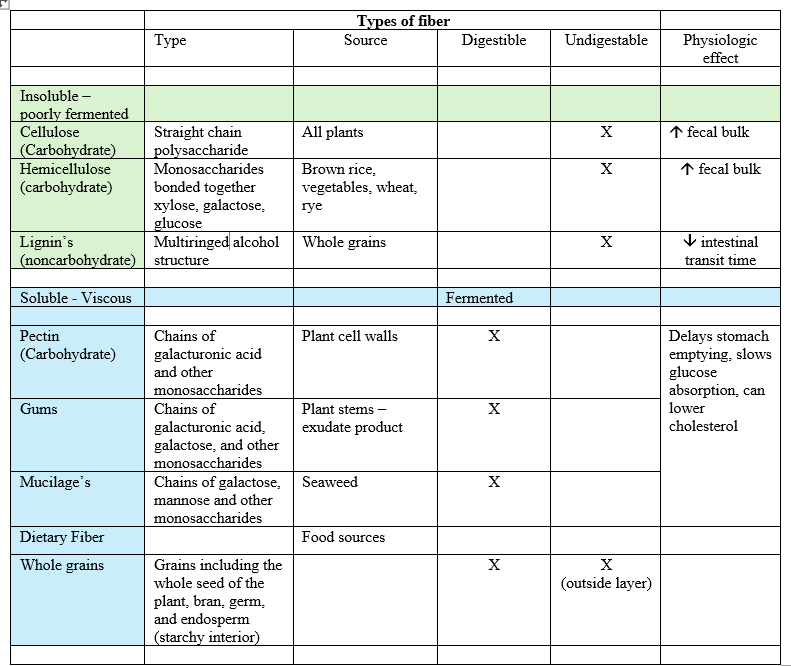

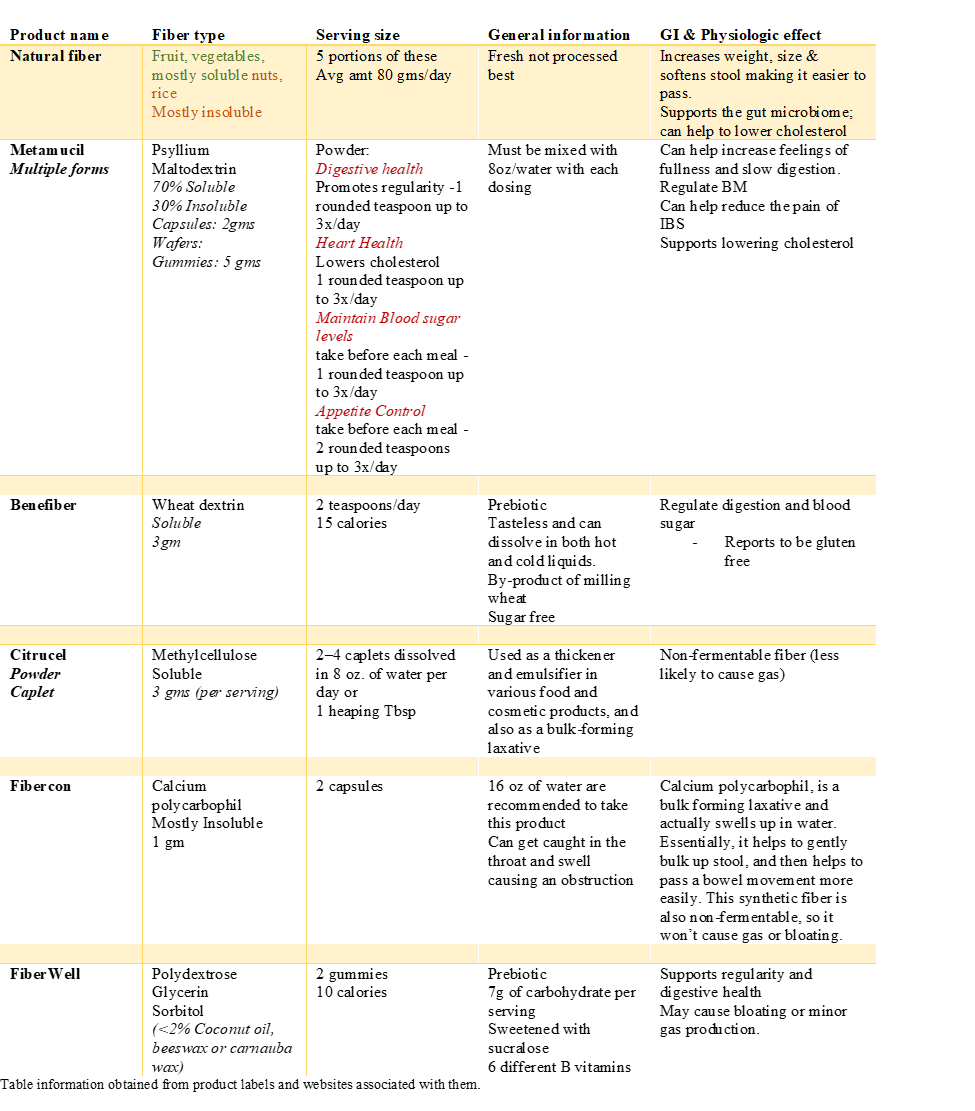

Fiber

Fiber (Table 5) is considered a “non-starch” and is a class of carbohydrates known as polysaccharides. These substances while having individual sugar units, cannot be digested by the enzymes (Table 5.1) in the human GI track. Because of this structuring, the sugars associated with the “fiber” are not able to be absorbed through the small intestine into the general circulation.

Table 5: Fiber

Table 5.1 Fiber Supplements

Water

Learning Objectives |

|

Parts of the water section adapted from Draper, Kainoa Fialkowski Revilla, and Titchenal (2020). Human Nutrition 2020e, University of Hawaii at Mānoa. LibreText. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nutrition/Human_Nutrition_2020e_(Hawaii)

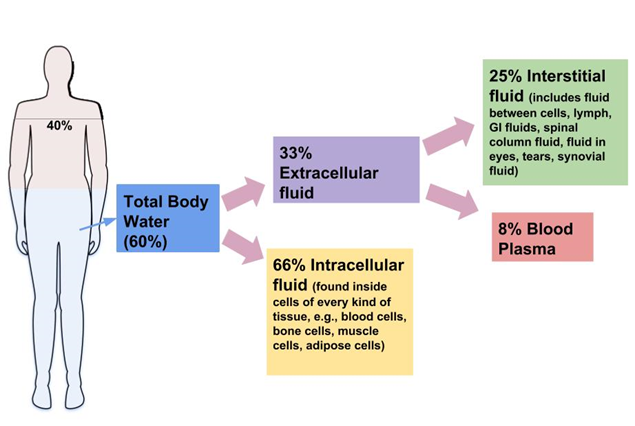

The human body is made up of mostly water. An adult consists of about 37 to 42 liters of water, or about eighty pounds. Adult males typically are composed of about 60 percent water and females are about 55 percent water. (This gender difference reflects the differences in body-fat content, since body fat is practically water-free. This also means that if a person gains weight in the form of fat the percentage of total body water content declines.) As we age, total body water content also diminishes so that by the time we are in our eighties the percentage of water in our bodies has decreased to around 45 percent. “Adults who stay well-hydrated appear to be healthier, develop fewer chronic conditions, such as heart and lung disease, and live longer than those who may not get sufficient fluids” (Dmitrieva et al., 2023, p. 8).

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance – a quick review

Although water makes up the largest percentage of body volume, it is not actually pure water but rather a mixture of cells, proteins, glucose, lipoproteins, electrolytes, and other substances. In the human body, water and solutes are distributed into two compartments: intracellular, and extracellular. The extracellular water compartment is subdivided into the spaces between cells known as interstitial, blood plasma, and other bodily fluids such as the cerebrospinal fluid (Figure 1). The composition of solutes differs between the fluid compartments. For instance, more protein is inside cells than outside and more chloride anions exist outside, of cells than inside.

Figure 1: Distribution of body fluids

Figure 3.2.2 : Distribution of Body Water. Image by Allison Calabrese / CC BY 4.0

http://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition2/

Osmoregulation

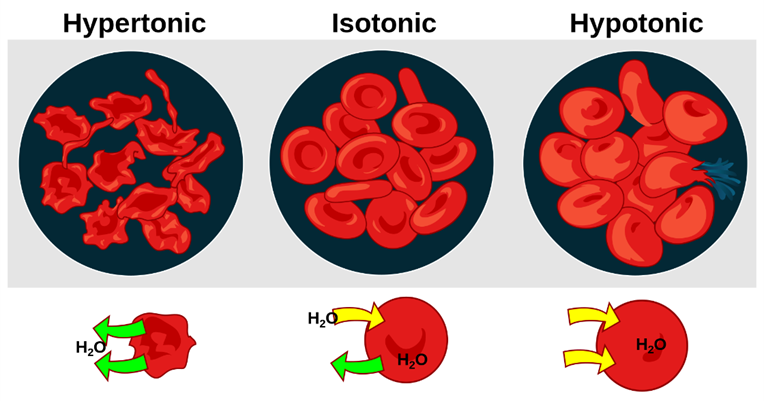

The movement of water between fluid compartments happens by osmosis, which is simply the movement of water through a selectively permeable membrane from an area where it is highly concentrated to an area where it is not so concentrated. Water is never transported actively; that is, it never takes energy for water to move between compartments. Although cells do not directly control water movement, they do control movement of electrolytes and other solutes and thus indirectly regulate water movement by controlling where there will be regions of high and low concentrations.

Cells maintain their water volume at a constant level, but the composition of solutes in a cell is in a continuous state of flux. This is because cells are bringing nutrients in, metabolizing them, and disposing of waste products. To maintain water balance a cell controls the movement of electrolytes to keep the total number of dissolved particles, called osmolality, the same inside and outside (Figure 2). The total number of dissolved substances is the same inside and outside a cell, but the composition of the fluids differs between compartments. For example, sodium exists in extracellular fluid at fourteen times the concentration as compared to that inside a cell.

Figure 2: Osmolarity

Figure 3.2.3 Osmoregulation. “Osmosis” by Mariana Ruiz / Public Domain

Water and health’s association

Hydration and the importance of it with respect to health optimization is often overlooked when it comes to nutritional recommendations and its nutritional association to health as well as its physiologic need. It is well known that an overabundance of water can perpetuate physiologic changes within the cardiovascular system, pulmonary, neurologic, musculoskeletal functioning and electrolyte imbalances. A human body is made up of mostly water. Of all the nutrients, water is the most critical as its absence over days can cause systemic alternations that can be life threatening. Water uses in the human body can be loosely categorized into four basic functions: transportation vehicle, medium for chemical reactions, lubricant/shock absorber, and temperature regulator.

Water Transportation:

The solvent action of water allows for substances to be more readily transported. Blood, the primary transport fluid in the body is about 78 percent water. Dissolved substances in blood include proteins, lipoproteins, glucose, electrolytes, and metabolic waste products, such as carbon dioxide and urea. These substances are either dissolved in the watery surroundings of blood to be transported to cells to support basic functions or are removed from cells to prevent waste build-up and toxicity. Blood is not just the primary vehicle of transport in the body, but also as a fluid tissue blood structurally supports blood vessels that would collapse in its absence. For example, the brain which consists of 75 percent water is used to provide structure.

Chemical reactions:

Water is an ideal medium for chemical reactions as it can store a large amount of heat, is electrically neutral, and has a pH of 7.0, meaning it is not acidic or basic. Additionally, water is involved in many enzymatic reactions as an agent to break bonds or, by its removal from a molecule, to form bonds. Water is required for even the most basic chemical reactions. Proteins fold into their functional shape based on how their amino-acid sequences react with water.

Lubricant/shock absorber:

Mucus is one of the most abundant lubricants in the body. Mucus is also required for breathing, transportation of nutrients along the gastrointestinal tract, and elimination of waste materials through the rectum. Mucus is composed of more than 90 percent water and a front-line defense against injury and foreign invaders. It protects tissues from irritants, entraps pathogens, and contains immune-system cells that destroy pathogens. Other protective water dominant products of the human body are the aqueous & vitreous humor of eye, cerebrospinal fluid and the amniotic fluid that surrounds a developing fetus, all of which function as a means to absorb pressure and protect underlying tissue.

Temperature regulation:

One of the major actions of water in the human body is to retain heat and act as a mechanism to change the bodies temperature. It takes a great deal of energy for a water molecule to change from a liquid to a gas, evaporating water (in the form of sweat) takes with it a great deal of energy from the skin (Haen-Whitmer, 2021)

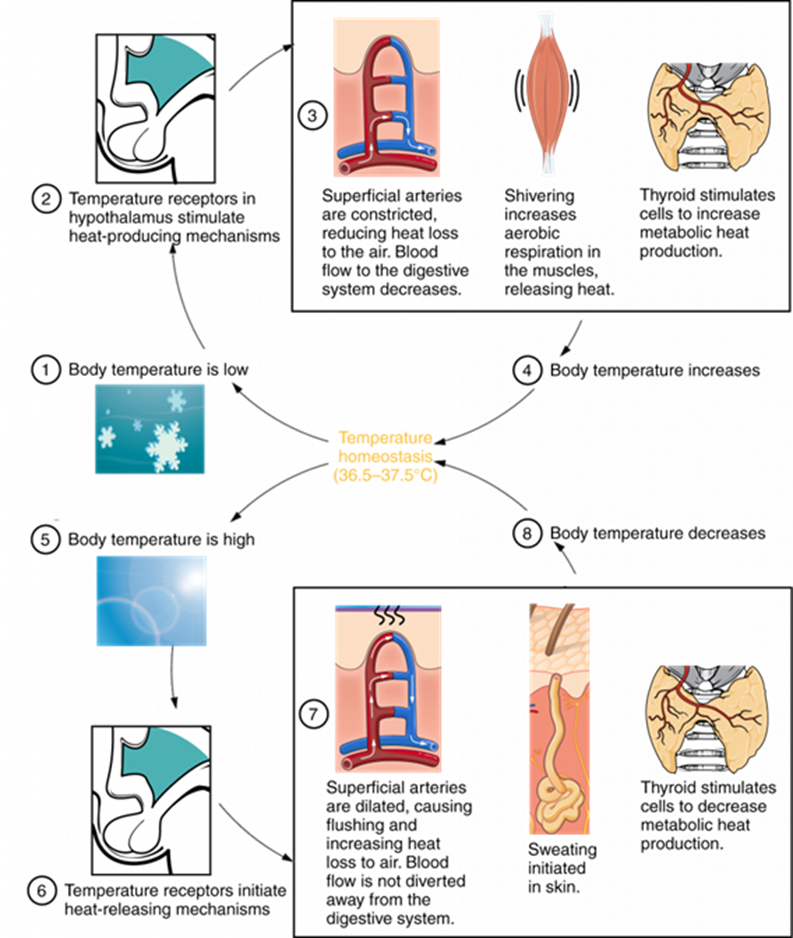

When the body becomes overheated, the body begins to sweat or perspire, which “evaporates through skin pores, releasing heat energy. So, as the water in perspiration evaporates, heat energy is removed from the skin, cooling the body in the process (Figure 3). In response to an increased body temperature, blood vessels in the skin become larger, allowing greater water loss through perspiration. Each quart (approximately 1 liter or 2 pounds) of perspiration that evaporates represents approximately 600 kcal” (Smith et al, 2022. p. 346).

Conversely:

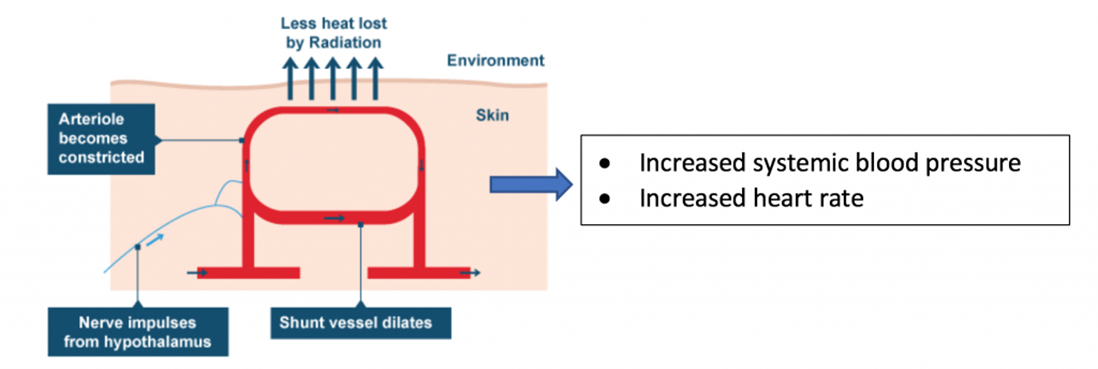

“Activation of the brain’s heat-gain center by exposure to cold reduces blood flow to the skin, and blood returning from the limbs is diverted into a network of deep veins (Figure 4). This arrangement traps heat closer to the body core, restricts heat loss, and increases blood pressure. If heat loss is severe, the brain triggers an increase in random signals to skeletal muscles, causing them to contract and produces shivering. The muscle contractions of shivering release heat while using ATP. The brain also triggers the thyroid gland in the endocrine system to release thyroid hormone, which increases metabolic activity and heat production in cells throughout the body” (Haen-Whitmer, 2021).

Figure 3: Cooling process of the body

Note: Hypothalamus Controls Thermoregulation. The hypothalamus controls thermoregulatory networks leading to an increase or decrease in the core body temperature.

Original image, OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology CC-by-4.0. Image edited by Aric Warner.

Figure 4: Physiological response to cold

Note: Physiological response to acute cold exposure. During acute cold exposure, the sympathetic nervous system releases norepinephrine, which results in vasoconstriction, increased blood pressure, and increased heart rate.

Original image, OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology, https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology.

Available for free under a CC-by-4.0 license.

Water and weight loss/weight gain

It is well known that the human body requires fluid to maintain life. Depending on geographic location there can be an abundance of clean drinking water available or very limited. In general individuals view the means for “hydration” to include a variety of beverage types ranging from electrolyte replacement such as Gatorade, soda, energy drinks, juices, teas/coffee products and water of varying of types (purified, alkaline, flavored, sparkling, tap and deionized). A key element to assess when evaluating fluid intake is what type of fluid is consumed and what are the ingredients, specifically the type of sugar or chemical additives. Typically, adult water intake should be about eight 8oz glasses of water a day and children/adolescents

Weight Intake: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2022) plain water intake less than 23 oz/day is found in “children, adolescents, non-Hispanic Black children or Hispanic children (compared to non-Hispanic White children), those living in lower-income households, youth whose head of household had less than a high school education (compared to college or higher)” (para. 2). This finding was also replicated in older adults with plain water intake being less than 44 oz/day.

Assessing water intake can easily be integrated as part of the nutritional assessment during an annual health promotion/prevention visit or a focused visit that warrants fluid intake to be assessed and provides an educational opportunity when a deficit is found.

Water and weight loss: There are numerous studies that have reported water intake supports weight loss in those seeking to lose weight along with abdominal adiposity (Çıtar Dazıroğlu & Tek, 2024; Shmerling, 2024; Zafar et al., 2024). Increasing water intake above the typically intake has been found to increase sympathetic activity which in turn has an intrinsic effect of increasing heart rate and metabolism. Drinking 8 oz of water before a meal increases stretch receptor activity in the stomach thus promoting a reduction of food consumption leading to reduced caloric intake. It has also been found that individuals who “snack” may actually be thirsty and drinking 8 oz of water abates the desire to eat leading to not eating “calorie dense foods,” reducing caloric intake, thus supporting weight reduction. Zafar et al., (2024) report a strong correlation between intestinal health, abdominal obesity, with post-meal fluid intake. There is controversy over increasing water intake before a meal versus after a meal and which is more effective in supporting weight loss (Shmerling, 2023; Suchitra et al., 2023). Even with inconsistency being reported in the literature as to when to intake water for the purpose of weight loss, one element is consistent with all, water does aid in weight loss for some individuals.

Water and weight gain: Frequently a patient will report that they have tried dieting and exercised and have not been able to lose weight. An important part of a diet lifestyle change is ensuring that the individual consumes adequate amounts of water to support proper metabolism of stored fat or carbohydrates. Dehydration or reduced water intake can extrude a negative effect on weight loss efforts and result in stalled weight loss or even weight gain. A person who drinks less than 500 ml of water a day is at risk for this occurring (Ensle, 2019). It is also important to remember that dehydration can make the body hold on to extra water to make up for the lack of incoming water thus impacting weight loss and promoting weight gain (Chin & Smith, 2024).

Assessing water intake and using as an intervention to support patient weight loss:

Current hydration state (amount of water/fluids consumed in a day) and products being used need to be evaluated

Diagnostics can be used to assess hydration state – Hgb/HCT, BUN

Comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, renal disease and hypertension etc. need to be assessed.

Patient use of medications such as diuretics, steroid use, antihypertensive's and any medication that can cause water retention need to be factored in.

Mobility and access to a bathroom evaluated.

Patient ability, desire to monitor/track fluid intake with an app to determine true fluid intake and increased fluid need. As well as patient engaging in this intervention correctly if chosen to do.

Utilize shared decision making