Petrarchan Sonnet

The Italian, or Petrarchan, sonnet arises from the Italian literary tradition but was popularized in the 14th Century by Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca), thus giving to its distinctive name. Sir Thomas WYatt and Henry Howard, earl of Surrey are credited with introducing Italian sonnets to England through translations of Petrarch's work. The adaptation into a sonnet sequence was popularized by Sir Philip Sidney's Astrophil and Stella, which was composed mostly of Italian-form sonnets (Sauer, 2008).

Petrarch excelled with this form, specifically writing about love, but as the poem matured to more complex and philosophical subjects, many other poets used this form as a means of expressing political views and religion.

The Petrarchan sonnet originated in Italy before eventually finding English poets such as William Wordsworth.

A key characteristic of Petrarchan sonnets is the blason, which can be either elaborate praise for the subject or excessive blame or scorn. And in describing the subject's beauty or the narrator's feelings, Petrarchan sonnets make extended use of metaphor and simile.

THEMES

The themes of a Petrarchan sonnet have a pattern. A problem or a sense of tension is introduced, then the question is resolved and the speaker feels a sense of peace.

CULTURE

The Renaissance gave birth to the Petrarchan sonnet, making the sonnet easy to express love or contemplative ideas. The concept of “rebirth” after the Middle Ages shed light on personal discovery, which made this poem form popular. Between the 14th and 16th centuries, the Petrarchan sonnet became increasingly popular for poets to express their feelings as questions. In a sense, this form of poetry is used by those looking to expressively work through a problem individually.

AUDIENCE

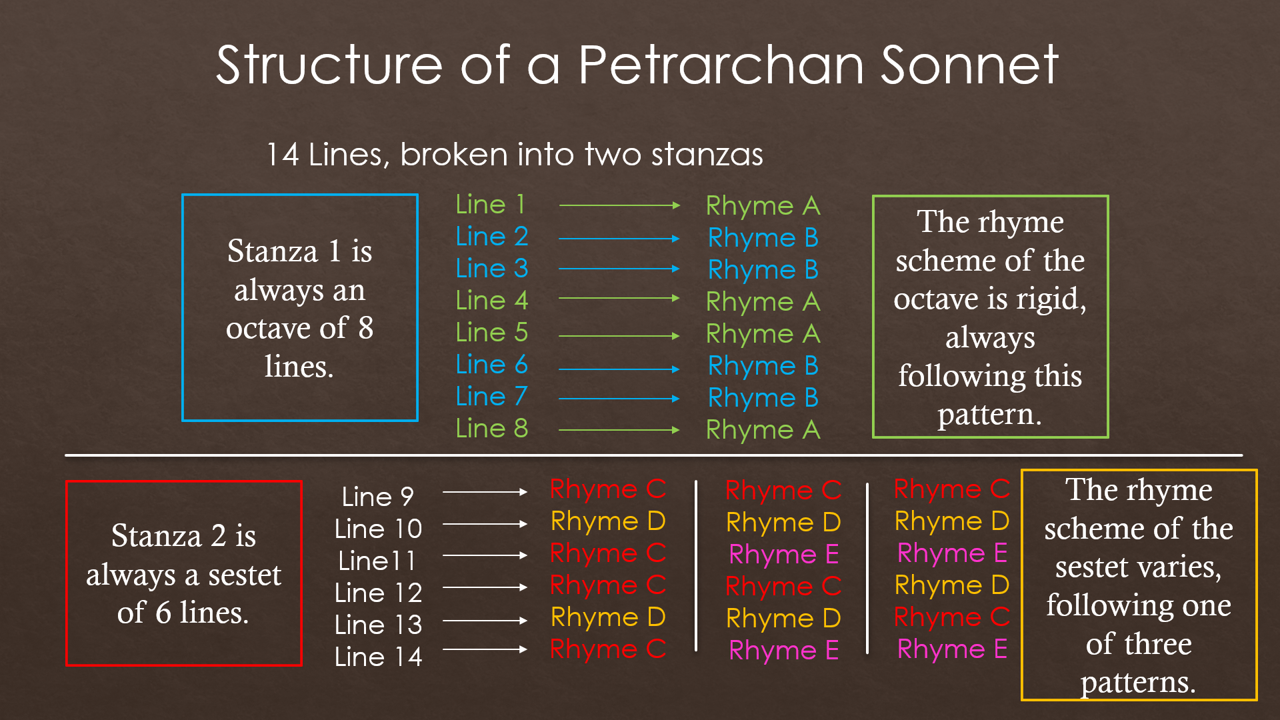

The audience is typically a love interest or, if the poem addresses an internal conflict, the audience would be the speaker and his thoughts. Petrarchan sonnets typically feature a recognizable “volta” or major turning point between the octave and the sestet, which is a breakthrough that the poet finds while talking about his internal question. These poems were meant for self-discovery; while an audience was not the focal point of the Petrarchan sonnet, this sonnet allowed poets to express emotions and work through individual problems.

To the Nile-by John Keats

Octave (8 lines) - introduces the problem or situation which leads to conflict or doubt in the reader.

A Son of the old Moon-mountains African!

B Cheif of the Pyramid and Crocodile!

B We call thee fruitful, and that very while

A A desert fills our seeing's inward span:

A Nurse of swart nations since the world began,

B Art though so fruitful? or dost though beguile

B Such men to honour thee, who, worn with toil,

A Rest for a space 'twixt Cairo and Decan?

Volta - the turn or transition found at the beginning of Sestet. Sestet (6 lines) proposes a solution to the problem raised.

C O may dark fancies err! They surely do;

D 'Tis ignorance that makes a barren waste

C Of all beyond itself. Thou dost bedew

D Green rushes like our rives, and dost taste

C The pleasant sunrise. Green isles hast though too,

D And to the sea as happily dost haste.