Introduction and Creation

Introduction and Creation

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Chapter One – What is Mythology?

Andy Gurevich

This week, we will begin to explore what myth is, no easy question to answer, and also look at some of the ways humans have developed and used their myths. We might discover as we go that the stories and mythological images of our ancestors speak to us today in more relevant and meaningful ways than we thought possible.

“Plaster sculpture of Apollo in medical mask” by Alena Shekhovtcova, World Mythology, Pexels is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Plaster sculpture of Apollo in medical mask” by Alena Shekhovtcova, World Mythology, Pexels is licensed under CC BY 4.0

First we need to try to define myth. One textbook offers a simple definition at the beginning of the introduction,

“Myths symbolize human experience and embody the spiritual values of a culture.” (Rosenberg xiii)

The problem with this definition is the phrase “symbolize human experience.” Just what does that mean? It is what myths do, but it doesn’t really give us much in the way of definition.

Joseph Campbell, another somewhat famous scholar and mythologist who we’ll be using often this term, defined myth as follows,

“A whole mythology is an organization of symbolic images and narratives, metaphorical of the possibilities of human experience and the fulfillment of a given culture at a given time.”

“Metaphorical of…” Hmm. What does that mean, exactly? Onward.

Psychoanalyst Rollo May, in his book “The Cry for Myth” suggests,

“A myth is a way of making sense in a senseless world. Myths are the narrative patterns that give significance to our existence. Myths are like the beams in a house: not exposed to outside view, they are the structure which holds the house together so people can live in it.”

You will soon see that although most scholars of mythology agree that it is a foundational component of how any society, culture, and individual define themselves, none can agree absolutely on how to define it. But this isn’t really a problem. They may all be right, given the aspects of myth they are emphasizing in their different definitions.

That is why I encourage you to define myth for yourselves during your readings and ponderings.

From the many definitions of myth in books and on the web, we can see that myths have four basic attributes in common:

- They are cultural—they reflect the beliefs and values of a group of people.

- They are sacred—they concern the spiritual or divine aspects of existence that human beings cannot understand.

- They are didactic—they seek to explain the unexplainable, and they teach humans how to behave, live, and relate to each other and the gods.

- They are foundational—they provide basic rules, beliefs, and rituals for a culture to establish shared beliefs and practices.

Joseph Campbell adds that all living myth must serve four primary functions:

- Cosmological—Its cosmological function is to describe the “shape” of the cosmos, the universe, our total world, so that the cosmos and all contained within it become vivid and alive for us, infused with meaning and significance; every corner, every rock, hill, stone, and flower has its place and its meaning in the cosmological scheme which the myth provides.

- Mystical—Its metaphysical function is to awaken us to the mystery and wonder of creation, to open our minds and our senses to an awareness of the mystical “ground of being.” Many would say that this is the primary function of myth-to find a way to communicate whatever mystical insight has been gained on the journey: an understanding of the mysteries that underlie the universe; an appreciation of its wonders; the sense of awe or rapture experienced. Since this experience often can’t be communicated directly, myth speaks in metaphors, symbols, and symbolic narratives that aren’t always bound by objective reality.

- Sociological—Its sociological function is to pass down “the law,” the moral and ethical codes for people of that culture to follow, and which help define that culture and its social structure.

- Psychological—Its psychological (or pedagogical) function is to lead us through particular rites of passage that define the various significant stages of our lives-from dependency to maturity to old age, and finally, to our deaths, the final passage. These rites of passage bring us into harmony with the “ground of being” (a term used by Campbell to refer to an unnamed, unspecified universal mystical power) and allow us to make the journey from one stage to another with a sense of comfort and purpose.

Today, in our culture, we often dismiss myth as a falsehood, or fanciful, untrue stories, like urban myths or “false news.”. This is not the definition of myth we will concern ourselves with. For each of the myths we read, the culture from which they arose believed them to be true and foundational to their individual and collective identities. It was how they understood the great mysteries of the universe and our place in it—How did the earth come to be? How was mankind created? What is my purpose? Can I know god? Is there a life after death?

Today, we are still asking the same questions, and for many people, the answers are in their religious beliefs, many of which have their roots in the myths. Campbell once said, “a mythology is another person’s religion, and a religion is your own personal mythology.”

This first group of myths (Lessons 1 through 4) are Creation myths. They seek to explain “how it all started.” There are 8 basic motifs (a recurring pattern or object) for creation myths:

- Conjunction: mingling of waters or primal elements creates a first entity or a livable surface

- Divine emission: blood or other body fluids create man or beings or other gods

- Sacrifice: a god sacrifices himself or is sacrificed to achieve creation of the earth or humans

- Division/Consumption: marriage of earth and sky or separation of earth and sky creates livable space for humans

- Cosmic egg: all humans, and the earth sometimes, are contained in a great egg to be opened when the god wills it

- Emergence: first “people” emerge from an original cramped or hostile world into a new world or a series of worlds

- Deus Faber: the god consciously crafts the world and humans out of a substance necessary for the survival of mankind (like clay, mud, stone, corn)

- Ex Nihilo-out of nothing: creation by thought, breath, dream or word

These eight methods are creation are easy to see in the myths we read. What might each method say to the people about their importance to the gods? Think about this question as your read the myths.

As you read, you will see that myths are narratives; they tell a story. It is the culture’s way of trying to explain the creation of the universe and mankind in a way everyone could understand. These stories (myths) were passed down through generations orally because they existed long before humans created writing.

We don’t know for sure, but it is likely that the myths evolved over time as they were retold, perhaps to include new myths from other cultural groups, or to reflect man’s more sophisticated understanding of the world and the gods.

Often these myths were retold in celebrations of a religious nature, such as a New Year celebration or the beginning of spring, or at the harvest.

The myths, although simple as narratives, are complex in trying to explain existence and the gods. In some cases, you will find contradictions, missing pieces, and some just plain confusing ideas. Remember, these are myths, not fact-based explanations. We need to read them differently than we would a history or science book. But when we know how to read them as intended, as metaphors for the journey of the soul back to the ground of its own being, then they can reveal timeless truth to us, whether we “believe” in them or not.

So…A closer look: It’s about time!

- Legend is defined as a traditional story that may be based on historical facts, but is not easily proven to be historical (like the legend of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table).

- Folklore is more like myth in that it is stories about traditional beliefs, customs, and stories of a community passed down through word of mouth. This definition is very much like myth, but as we will see, there is one attribute of myth that may be missing from folklore.

In the Indian (Hindu) creation myth, time is presented as cyclical—a constant repetition of creation, destruction and rebirth. The Mayan culture also saw time as cyclical as presented in their calendars. Most Western religions have from their beginning seen time as linear, having a clear, set beginning (On the first day, God created…) and a clear, set ending. When our world ends, there is no indication that there will be a regeneration or re-creation as there is the Hindu myth.

Yet, everything about our world indicates that time is cyclical—the track of the sun and moon through the sky, the passing of the seasons, the celebration of recurring events like Thanksgiving and our birthdays, even our clocks are round.

Time is one of those puzzling questions that underlies many of the great questions of mankind. We are obsessed with time, and much of our language is devoted to time—we try to save time (a bizarre notion); we spend time; we think time is money; we take time; we waste time. We even upset our lives twice a year by setting clocks ahead and back.

Scientists and philosophers tell us time is an illusion, it isn’t real, and we can’t measure it. Why then does it seem so real to us? We can’t function without schedules, or knowing what time it is.

So, think about this: how might believing in time as linear or cyclical influence a culture’s attitude toward death or how we live our lives in the present time? What if we do come back for another try? What if X marks the spot and when we get there, there is no hope to return to life as we know it?

Now you are ready to read the myths (Please do not panic. Many of these are quite short and you can use open book and open notes to do your assignments.):

- The History & Functions of Myth

- The Enuma Elish: Historical Context

- The Babylonian Creation Epic: The Enuma Elish

- Click here for another version of the myth.

- The Mayan Creation: Introduction and Historical Context

- THE CREATION (Mayan)

- Click here for a video version.

- The Chinese Creation: Introduction and Historical Context

- The Creation Myths:

- Pan Gu

- Nu Kua (or Nu Wa)

- Yin and Yang

- Click here for an alternate version of all three.

- The Creation Myths:

- The Indian Creation: Introduction and Historical Context

- The Hindu Creation Myths

- Alternative video versions of the Hindu Creation:

Chapter Two – Myth & Metaphor

Andy Gurevich

The Greeks believed human thought functioned through two separate avenues, Logos and Mythos.

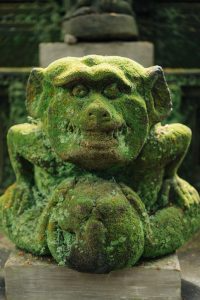

“Stone mythical creature statue in jungle” by Nick Bondarev, World Mythology, pexels is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Stone mythical creature statue in jungle” by Nick Bondarev, World Mythology, pexels is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Logos is the analytical, logical method for dealing with the information and complexity of the world. It is governed by “rules” such as we still use in arguments and more formal logical exercises.

Then there is Mythos which follows our basic definition of myth: a collection of stories and beliefs held in common by a group of people. Unlike Logos, Mythos deals with non-logical, non-concrete, non-linear aspects of the world and our psyches. There are not rules governing how we interpret myths as they often deal with those things outside the realm of human consciousness and understanding.

The way that we can attempt to explain the unexplainable, those things beyond the world of Logos, is through metaphor. It takes a little work to wrap our heads around this concept, but it is important in helping us understand how to interpret the meaning of the myths. This idea of metaphor is not without controversy; it encourages us to view myths (and religion) in a different way. I ask you to read and consider before you judge.

Let’s start with a simple definition of metaphor: it is a comparison between two different things without using the words “like” or “as.” Simple, right? Maybe not so simple. Here is a comparison using like or as:

My love is like a red, red rose.

This clearly states a comparison, but let’s look at it as a metaphor:

My love is a red, red rose.

Makes a difference, doesn’t it? What the metaphor does is invite us to take the statement literally; we sometimes miss the idea of a comparison.

Let’s look at another metaphor:

He is such a snake in the grass.

This we know not to take literally. The metaphor suggests a comparison between the person and the qualities or attributes we associate with snakes (evil, dangerous, slimy). Furthermore, we know that not all snakes are dangerous, and they are evil only because we are using the snake as a metaphor. The snake’s association with evil is cultural. (More about snakes in the future.) So our metaphor—he is a snake—invites us to attach various ideas about the man through associating him with ideas we have about snakes, whether they are accurate or not.

We use metaphors every day to describe our feelings (I’m feeling blue) our troubles (My life is a train wreck) our happiness (I’m on cloud 9). Our dream are metaphors (dreams of flying, being chased, demons). We too often take our metaphors literally.

Myths are metaphors. The whole myth is a method of trying to convey things we don’t understand in a way that we can begin to understand. How must it have felt, before science and technology, to look up at the night sky and try to explain all those points of light? Or how do you explain the phases of the moon and its disappearance for three days? Even with a “scientific understanding” of the world, myths help us to create narrative containers for the awe we feel at the very mystery of existence itself. And metaphors are the primary vehicles of myths.

The use of metaphor helped ancient cultures understand. They created pictures with the brightest stars and named them after their gods. The moon became the goddess, dying and being reborn, just like the crops in the spring. The metaphors tied humans to the earth and the gods; they were both a part of creation, and separate from the gods.

Have a look at a illuminating encounter the late mythologist Joseph Campbell had with a radio host about the concept of metaphor by clicking here.

So, to sum up the main points:

“Crozier Head (ca. 1350)” by Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917, The Met Museum is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Crozier Head (ca. 1350)” by Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917, The Met Museum is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Metaphors suggest comparisons, although they don’t explicitly state a comparison.

- Myths are metaphors.

- Metaphors can often reveal truths that are deeper and more lasting, but harder to unpack.

- We cannot take the metaphor (or the myth) literally and expect to understand its full symbolic value.

Now you are ready to read the myths:

Chapter Three – Myth & Archetype

Andy Gurevich

By now, you have most likely noticed that there are common ideas, themes or objects that recur in some of these myths. Take the flood, for example. If you look at myths from across the globe, almost all of them have a flood story of some sort. How can we explain this?

“The Deluge (ca. 1630–38)” by Pierre Brebiette, The Met Museum is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“The Deluge (ca. 1630–38)” by Pierre Brebiette, The Met Museum is licensed under CC BY 4.0

One way is that these myths contain a historical account of a great flood. We know there was a huge flood in the area of the eastern Mediterranean Sea into the Black Sea. Depending on the source, it happened anywhere from 11,000 BC to 3,000 BC. It is possible as the last great ice age ended, it did inundate this area. Check out this Historical Evidence for the Great Flood.

But areas that are far inland, high in elevation and otherwise not likely to be flooded have these deluge stories too. How can historical fact explain this? Archeologists are fairly certain that the entire globe was not under water.

Another explanation may be that through trade routes or conquest, these stories were shared with new populations who found them so compelling they incorporated these myths into their own. Again the same problem presents itself: were there trade routes between, say, Greece and Argentina or the southwestern United States. It is unlikely. Remember these early societies did not have Facebook or Twitter; in fact, they were unaware the rest of the globe even existed.

One explanation that fits nicely, although there is no real proof in the scientific sense, is the idea of archetypes and the collective unconscious. These ideas were put forth by the 20th century psychiatrist, Carl Gustav Jung. His ideas are highly speculative, but they do offer an avenue for studying these recurrent ideas we see in myth.

Basically, what Jung said is that there exists in every humans mind the collective unconscious. This is the area of our psyche where dreams and myths are stored. They contain themes and ideas that humans have had in common since the beginning of human existence. We can see these ideas and themes in the myths: the flood, the creation of man from clay (or other substance that is critical to sustain life), symbols like the world tree, or the world egg. These common symbols, themes and patterns are called archetypes. To clear up the difference:

- A symbol is an object that stands for something else or calls that something else to mind. A symbol is cultural, shared by a group of people. We do not naturally understand what a symbol means; we must learn its meaning. The alphabet and language are symbols. The logos of companies are symbols. Like the Nike swoosh, we need to learn to associate the symbol to what it is referring to (its referent).

- An archetype is a symbol that is not tied to one culture. It is shared by all cultures, across time. We can readily see, and respond to, archetypes we see in movies: the villain, the hero, the wise old man (The Lord of the Ringstrilogy is a good film to see archetypes). Archetypes can also be objects-the circle, the mandala. They can be themes-the heros journey, travel to the underworld, fighting dragons (or some such creatures). The thing that distinguishes archetype from symbol is that all humans respond and understand the archetypes in similar ways.

If we think back to myth and metaphor, it may be easier to understand the idea of the collective unconscious and archetype. Our myth and dreams are metaphors and they use the archetypes to manifest themselves to us. That accounts for the similarity of the ideas and symbols in myths and our dreams. So as an explanation for the existence of myth across the globe as well as the commonality of the ideas and symbols in myth, this explanation serves a purpose.

“Old carved metal lion head sculpture” by Plato Terentev Follow Message, World Mythology is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Old carved metal lion head sculpture” by Plato Terentev Follow Message, World Mythology is licensed under CC BY 4.0

It’s an interesting look at the consciousness of mankind. We are really linked in our myths and dreams. Carl Jung says these symbols are never clearly defined or fully explained, as they are part of the unconscious. We can learn the meaning of archetypes, but they become understandable only on an individual basis. Again, Jung says that archetypes are, at the same time, image and emotion. When there is merely the image, then there is a word-picture with little consequence, but when charged with emotion, it becomes dynamic.

I think of the Goya picture of Cronus devouring his children. It is both an image that is symbolic, but also arouses deep emotional responses. Think also of those images we relate to evil, like snakes. Many people are afraid of snakes, spiders, bats--things we fear and associate in ways with evil and danger. That’s how an archetype works. We unconsciously associate the image and emotion and respond.

(For more information on archetypes and the collective unconscious, see Man and His Symbols edited by Carl G Jung. Material on Jung is from this book.)

The myths for this week:

Chapter Four – Myth & Meaning

The collaborative construction of mythological meaning.

Andy Gurevich

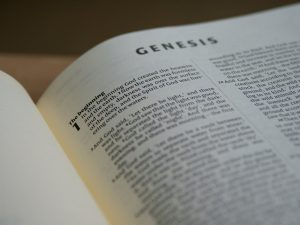

Genesis is apart from other myths in that it has one god only; he is all-powerful and all-knowing, and doesn’t seem to have the usual human-like failings of gods from other myths.

In a monotheistic belief system, God is generally removed from the people and is perceived as the creator who grants us life but demands pretty strict obedience.

“Close-Up Photo of Bible” by Brett Jordan, World Mythology is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Close-Up Photo of Bible” by Brett Jordan, World Mythology is licensed under CC BY 4.0

If we proceed with the idea that myth is metaphor, let start with “on the first day”—is this literally a day as we experience it? Since we can’t really know God, how can we know what a “god-day” is? So, is it literal or metaphor?

After God creates the world, animal and plants, he creates Adam and Eve. There are two different accounts of the creation of Adam and Eve in Genesis:

- The first, Chapter 1, lines 26 and 27, has God creating both Adam and Eve in his own image.

- Then in Chapter 2, lines 7 and 21-23, we get the more familiar story of Adam being created from the earth and Eve being created from one of Adam’s ribs. This picture of God giving life to Adam is part of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City. It is a Renaissance metaphor for creation. (You can see more images of the ceiling on line.)

Bible scholars agree that there were two authors of Genesis, referred to as J-E and P:

- J-E used the name Elohim (lords) and referred to god as Yahweh.

- The P version is believed to have been compiled for use by the priestly class.

The stories merged somewhere around the 6th to 7th centuries BC:

- The older version calls to mind many of the creation myths we have read so far.

- The second version of the creation of Eve from Adam’s rib is unique. Do we take these literally? I think an important question to ask is why such a reversal here? A woman is born from man! (That’s the metaphor).

The next big metaphor is the temptation by the serpent and the loss of the Garden of Eden for Adam and Eve.

Our archetypal serpent plays an interesting role here. The serpent symbolizes many things, from evil (probably best elaborated in Genesis) to rebirth (it sheds its skin).

Keeping this complex symbol in mind, what does the snake actually accomplish? It tempts Eve to eat the fruit from “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil,” despite God’s warning that if they ate of this tree (which is in the center of the garden) they would “surely die.” If this is so, why does Eve eat it and tempt Adam? Notice it didn’t take much to get Adam to go along with this.

In the picture below, we can see the metaphor clearly. Notice that Adam and Eve here have covered themselves before they have eaten of the fruit. Genesis clearly tells us that they ate, then they became ashamed of their nakedness, and then covered themselves. This picture shows the force of the metaphor on the human imagination.

“Adam and Eve (1504)” by Albrecht Dürer, The Met Museum is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Adam and Eve (1504)” by Albrecht Dürer, The Met Museum is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This tree is a great metaphor. Did Adam and Eve have no knowledge of good and evil before they ate? Let’s go beyond the metaphor—what does it mean to have no knowledge of good and evil? This is an important idea to think about. By eating the fruit, they became ashamed of their nakedness (another metaphor) and they hid from God. But God knows all, so, of course, they disobeyed and were served punishment and kicked out of the garden. If god is all-knowing, did he know they would disobey?

There is a theme in myth of the one forbidden thing—Pandora’s box is a good example. It is human nature to be told not to do something yet feel compelled to do it. Have you ever done something forbidden? Don’t we feel a complex of guilt and exhilaration that we did it, even though we knew we shouldn’t? The unspoken lesson we take from this is don’t disobey god, but it also explains why life is so hard. The punishment accounts for the submission of women to men and the hard work we have to do just to be alive.

But it also casts a new light on innocence (no knowledge of good and evil) and awareness of it. Why is knowledge of good and evil such a bad thing? Does it make us god-like in some way? If you remember from the Mayan myth, the gods clouded the vision and reduced the wisdom of their “perfect” creations. What does god say to Adam and Eve when he discovered their disobedience?

This myth, more than telling a story, causes us to ponder very big ideas—the role of knowledge of good and evil—does that make us god-like? It certainly suggests that the fall from the Garden was a loss of a golden or perfect age, maybe like the first yuga in the Hindu cycle. God also makes sure Adam and Eve couldn’t re-enter the garden. What reason does he give? Think about this on top of everything else!

This myth informs millions of people about their nature, our relationship to god, our relationship to each other and the world we live in. If we go beyond the metaphors, we can see the degree to which this myth has meaning for the way we live our lives.

We can do this with all the myths; it’s easier to see with Genesis because many of us are familiar with it. For an online copy of the King James version of Genesis, go to: Genesis-Chapters 1, 2, and 3.

Wanadi

Now to Wanadi. This myth is unique in a few ways. If you read the introduction in the book, you know that the Yekuhana were so isolated that they were never conquered or Christianized. This makes the myth clean of outside influence.

The myth in some ways reflects some Christian beliefs, the idea of a last judgment, the duality of good and evil, to name a few. But it has a quite unique view of reality.

“Blue Yellow and Red Abstract Painting” by Mikhail Nilov, World Mythology is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Blue Yellow and Red Abstract Painting” by Mikhail Nilov, World Mythology is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Briefly, this myth is pretty clear cut—it explains the existence of evil, how living beings were created (Was Wanadi smoking just tobacco?) It outlines how man should live his life and what happens at death. It does pose an interesting view of what is real.

But what Wanadi does is answer questions. Genesis, on the other hand, perhaps raises more questions than gives answers. Myth will often do this as well. Forcing us to dig deeper into it, and into ourselves, to uncover its more precious and lasting meaning and relevance.

Readings:

- The opening chapters of Genesis (also linked above)

- History of Greek Myth

- History of The Ages of Man

- History of Venezuelan Myth